GoldenRod Streamliner – Wheel-Driven Land Speed Rocketship

The land speed record has always been the Holy Grail for speed-addled enthusiasts. Prior to the advent of jet-engine machines, wheel-driven racers were the LSR standard bearers. Case in point: In 1947, Englishman John Cobb set the LSR record at 394.196mph, courtesy of a pair of Napier Lion VIIID WWII aircraft engines.

That record stood until 1963, when 27-year-old Craig Breedlove strapped himself inside his Spirit of America – a swoopy three-wheeled streamliner propelled by a GE J47 engine. Thanks to its 4,500 pounds of thrust, the turbojet moved the Spirit across the salt flats at a head-slapping 407.447mph, a new record.

But there has always been something a little untoward about simply letting jet power do the job. Traditional Bonneville racers believed that only internal-combustion, wheel-driven cars were legit. Sure, it may have worked for Wile E. Coyote, but purists like Mickey Thompson thought otherwise.

In the same camp were two brothers from Ontario, California – Bob “Butch” and Bill Summers – a couple of SoCal hot rodders who decided to reclaim LSR honors with an automotive-engine driven machine. It was an effort that melded old-school knowhow with aerospace and wind tunnel technology.

In the same camp were two brothers from Ontario, California – Bob “Butch” and Bill Summers – a couple of SoCal hot rodders who decided to reclaim LSR honors with an automotive-engine driven machine. It was an effort that melded old-school knowhow with aerospace and wind tunnel technology.

The original concept the Summers brothers dreamed up employed four 426c.i. Chrysler Hemi V8s set in two rows, side by side. After consulting racing equipment pioneer Tony Capanna, the design was changed, positioning the V8s all in a row. This allowed the engines to coordinate as a single 32-cylinder motor.

The normally aspirated Hemis were essentially stock except for fuel injection, and the total output of all four engines approached 3,000-horsepower. Two engines drove the front wheels, two powered the rear. Perhaps more importantly, the inline alignment offered another benefit – it meant the car itself could be narrower for less drag.

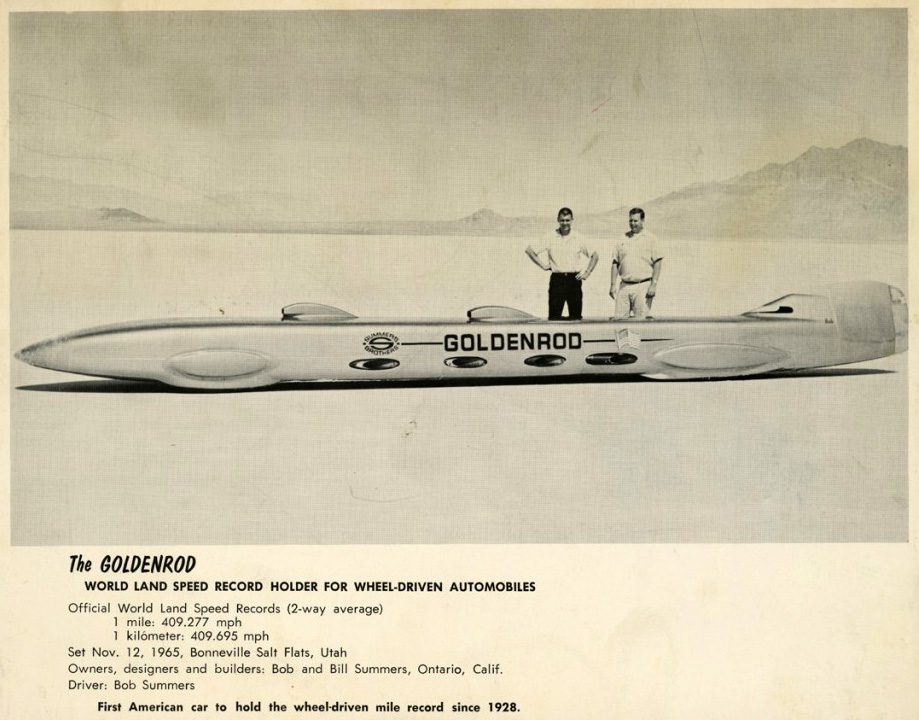

The quest for a sleeker profile led them to Lockheed engineer and aerodynamicist Walter Korff. With his input, the team created a pencil-thin, 32-foot-long streamliner. It measured a mere 48-inches wide, 42-inches high (at the tailfin), and 28-inches tall at the engine covers. They named it Goldenrod. The shape’s aerodynamic efficiency was then refined in Caltech’s 10-foot wind tunnel. The resulting drag coefficient was a remarkable 0.1165, one of the lowest ever achieved for a car.

While all this seemingly high-tech engineering hinted at a well-funded, sophisticated effort, it was more seat-of-the-pants hot-rodding than it appeared. Moreover, by today’s standards, the Goldenrod was a budget ride, costing a paltry $250,000. And even that sum was a challenge to raise.

Eventual sponsors included Hurst Performance; Firestone Tire & Rubber, which made special low-profile tires to fit inside the narrow body; Chrysler Corporation, which “loaned” the four Hemis; and Mobil Oil, which provided fuel and funding. Construction on Goldenrod began in January 1965 in a makeshift building that once peddled produce. Eight months later it was finished and a month after that the brothers were at Bonneville, where for two months they worked out various details in preparation for a trial run.

On November 12, Bob Summers ignited the four Hemis, floored the throttle, and hung on. As scenery quickly blurred around him, he followed Bonneville’s famous black line all the way through the speed trap – at an unprecedented 417mph, which was 23 mph faster than Cobb’s 18-year-old record.

To ratify the record, the rulebook required two runs, in opposite directions, within 60 minutes. The brothers double-checked everything thoroughly, Bob climbed in once more. With a scant five minutes to spare, his second run was good enough for a two-way average of 409.277mph.

Soon thereafter, rules makers split LSR records into two separate categories, jet-powered and wheel-driven. While jet cars soon eclipsed the Summers Brothers record, the Goldenrod held the title of world’s fastest wheel-driven automobile from 1965 to 1991. Its enduring record meant the Goldenrod never returned to Bonneville; there was no need. Then the show circuit beckoned, and it was displayed across America and Europe before ending up parked outside at the NHRA Museum in Pomona, California. In 2002, The Henry Ford museum purchased the car from Bill Summers.

Sadly, time – and salt – had taken its toll on the beautiful machine. Key components had been corroded, others missing altogether. The brilliant golden hue had faded. A full restoration was in order. The museum applied for and secured a Federal grant (Save America’s Treasures) to return it to its record-breaking glory.

Sadly, time – and salt – had taken its toll on the beautiful machine. Key components had been corroded, others missing altogether. The brilliant golden hue had faded. A full restoration was in order. The museum applied for and secured a Federal grant (Save America’s Treasures) to return it to its record-breaking glory.

Again, it was two SoCal hot rodders that took up the challenge: Former Hot Rod Magazine editor John Baechtel of Landspeed Restorations and Mike Cook of Cook Motorsports. The restoration was spot on – Chrysler even returned the four Hemis. The Goldenrod has been on permanent display at The Henry Ford since 2006, cementing its status as a true legend of hot rodding.