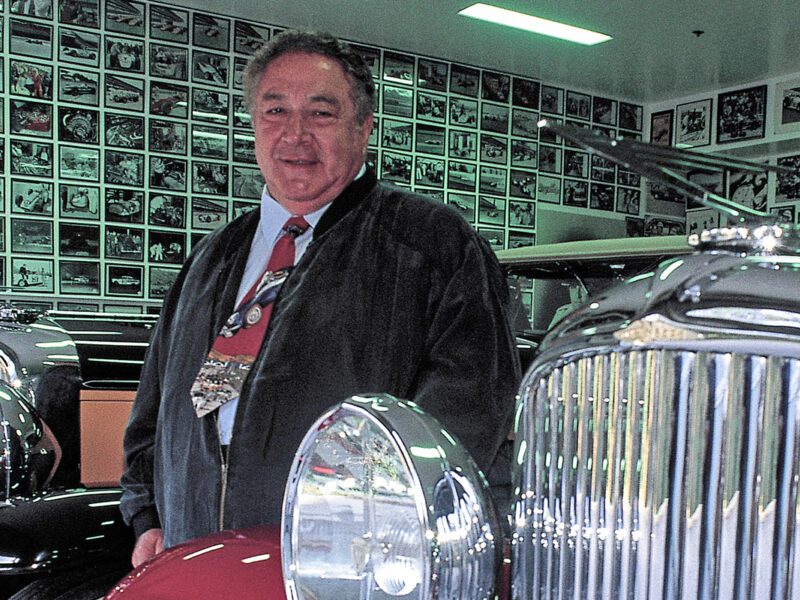

Bruce Meyer – Keeper of the Flame

Bruce Meyer never built a hot rod. Never assembled a Flathead. Never painted flames or pulled a pinstripe. Yet, when the history of hot rodding in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is written, Meyer’s contribution will long be remembered – for few people have committed themselves to the preservation of hot rod culture as has Meyer.

Meyer was born in Hollywood in the early 1940s. His parents – dad was an appliance salesman – believed cars were a waste of time and money. Unbeknown to mom and dad, though, the elementary school their son attended was adjacent to the Los Angeles Art Center parking lot – which was filled with hot rods, many owned by students who had returned from WWII. These vets were fueled by the G.I. Bill and a passion for fast cars. Roadsters were the vehicle of choice, and by the age of six, Meyer vowed to own one someday, too.

A hot rod may have been out of the question, but later Meyer secretly bought a 1950s BSA scrambler for a hundred bucks. He kept it stashed in a friend’s garage, away from his parent’s disapproving eyes. They never figured it out.

Fast forward a decade and teenage Bruce, a smart kid, attended UC Berkeley during the hippie era. He did his part, opting for flowing, shoulder-length hair. He earned a bachelor’s degree in business and hustled side jobs to supplement his student loan. He also figured out how to “work” the university’s interest-free student loan program. Meyer borrowed money, but not for books or study abroad. Rather, he bought motorcycles, raced them on the weekends, and then flipped them for a profit. Yeah, smart kid.

By this point, Bruce’s father had opened a boutique in Beverly Hills called Geary’s, and Bruce convinced his dad to include candles and incense. Soon, Meyer had his own store. While a moneymaker, a turning point came when he purchased the building itself. This led to a long career as a real estate developer across Southern California, which afforded him the opportunity to pursue his other passion – automobiles.

In college, Bruce had picked up a new Porsche 356 coupe ($2,700), which led him to a long involvement in Porsche culture. He sold it and bought a Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing with a Corvette V8. The Mercedes started three decades of car collecting, European and American classics.

In college, Bruce had picked up a new Porsche 356 coupe ($2,700), which led him to a long involvement in Porsche culture. He sold it and bought a Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing with a Corvette V8. The Mercedes started three decades of car collecting, European and American classics.

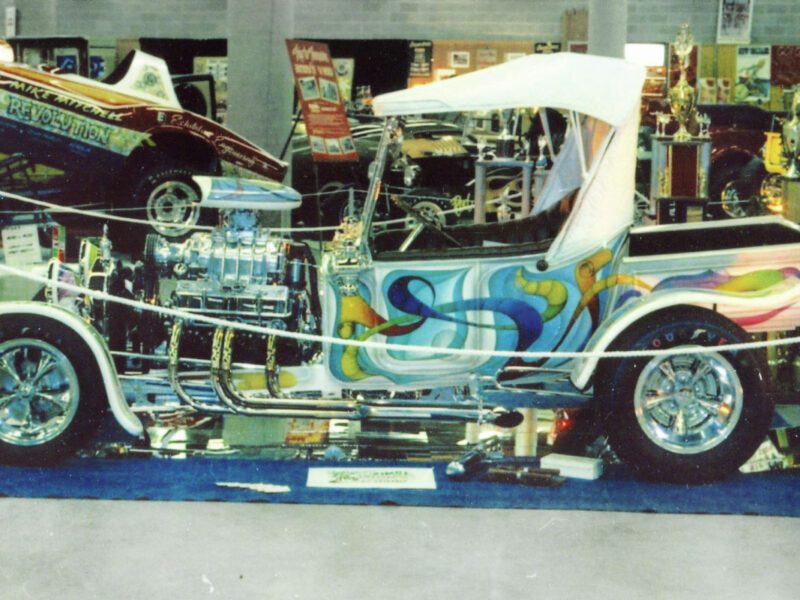

The collection is now Jay Leno worthy. Here’s a sampler: Ferrari 625/250 Testa Rossa, the first production Shelby Cobra ever built, 1965 Iso Bizzarrini AC/3 Competition, 1960 Chevrolet Corvette LeMans entry, 1957 Ferrari Testa Rossa raced by Richie Ginther, the Greer/Black/Prudhomme dragster, the Le Mans-winning 1979 Kremer Porsche 935 K3, and Dan Gurney’s ’32 highboy. And there’s more, many more.

Along the way Bruce befriended Robert Petersen, publisher of Hot Rod magazine. Together, they partnered with the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum to establish the now-acclaimed Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles. Meyer became its first chairman, and today the Bruce Meyer Family Gallery features many cars from his private stock.

Yeah, but what about hot rods? Meyer realized early on that the post-WWII SoCal hot rod scene – the Art Center parking lot being just one example – is a historically significant, if under-appreciated, chapter in American popular culture. This belief was deepened when he became friends with Alex Xydias and Pete Chapouris.

The trio combined to restore one of the most famous hot rods of all time, the Xydias Belly Tank. In addition, Meyer has also been particularly smitten by ’32 Fords. He has collected eight of the most significant Deuces of all time – the Bob McGee roadster, Doane Spencer roadster, Bob Morris roadster, Lobeck-Coonan-Bauder-Meyer roadster, Cook-Benish-Meyer coupe, Doyle Gammell coupe, Tom Prufer coupe, and the Larry Roller coupe, plus the Gurney ’32. This collection was immortalized in the book, “Deuce! 1932 Ford Hot Rods from the Bruce Meyer Collection,” by historian Ken Gross.

Now a spry, indefatigable 82 years old, Meyer still lives life guided by the credo suggested to him by Indy 500 winner Parnelli Jones – “Never lift!” We recently spoke to him by phone from the UK, where he was attending a classic car event.

“It’s hard to overestimate just how large a role hot rods played in 20th century American culture,” Meyer said. “Part of my interest in preserving these cars is to honor, not just the car owners, but the craftsmen who built them. All these WWII heroes, who had learned different skills in the service, came back and created timeless examples of automotive art. I wanted to make sure that appreciation is remembered by future generations.”

Former chief class judge at Pebble Beach concourse Winston Goodfellow perhaps summed up Meyer best when he told Mark Vaughn at AutoWeek, “What he has is an appreciation of history and an understanding of where things fit in it.”

As for Bruce Meyer himself, he fits in nicely as a true legend of hot rodding.