Jack Chisenhall’s ’53 Studebaker – To Air is Human. To Go 200mph is Divine.

One could argue that street rodding’s popularity after the first Street Rod Nationals was propelled not by ’glass bodies, aftermarket suspension bits, or crate motors. Rather, that growth was driven by something far simpler – cool air. Air conditioning made driving a hot rod in summer much more pleasant. And one man was instrumental in popularizing this innovation: Jack Chisenhall of Vintage Air.

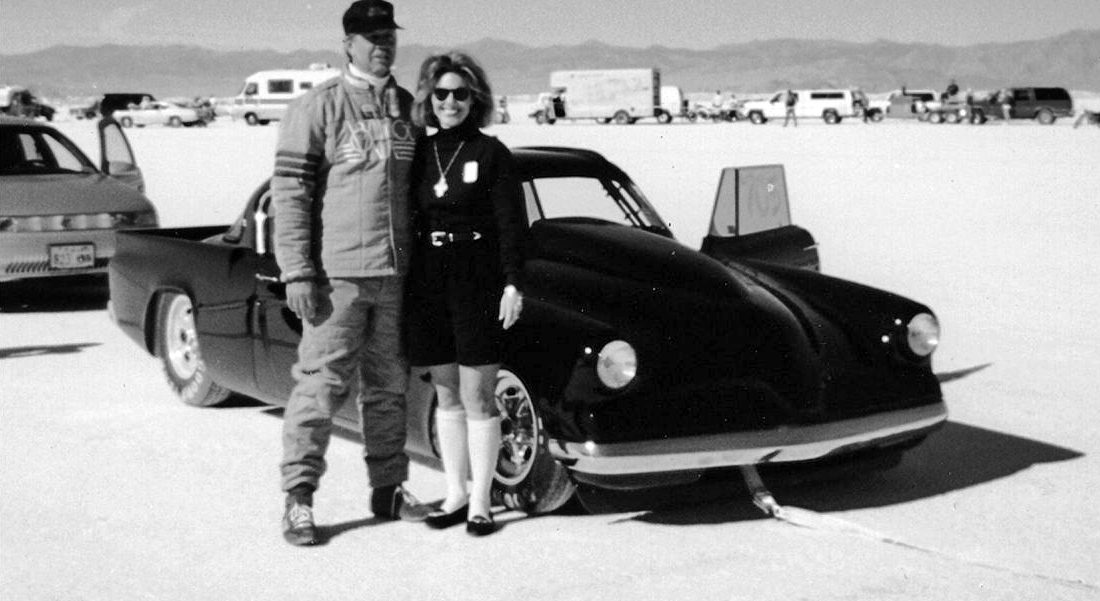

But there is more to Chisenhall than being an aftermarket pioneer. He is also a racer, with a deep interest in the roots of the sport, including Bonneville. Thus, he was drawn to putting together a really fast salt flats car that would also be street legal – and feature air conditioning.

His choice of car was easy: A mid-50s Studebaker coupe. His family was a Studebaker family. “My father always owned Studebakers and my uncle worked in a Studebaker dealership,” Chisenhall explained. “I drove one in high school,”

It didn’t hurt that mid-’50s Studebakers featured one of the most stylish and aerodynamically slippery profiles of the era. The result was Chisenhall’s “Cool 200” ’53 Studebaker coupe, one of the most spectacular – and fast – rides ever assembled.

The project started with a woebegone ‘53 coupe sourced in small-town Texas and dropped off at Bill McCall’s shop in San Antonio. Designer Larry Erickson (of Cadzzilla fame) penned a rendering. One clever addition to the ’53 was the addition of ’56 Studebaker Golden Hawk fins, which were taller than the ‘53 and increased high-speed stability.

To build a rigid foundation, Chisenhall designed a NASCAR road-race style chassis, employing 3×4-inch rectangular tube frame rails and a full round-tube roll cage, with the side tubes lowered to ease ingress and egress. Being a dual-purpose street-and-race machine, a four-speed transmission was mated to a quick-change differential that could accommodate both straight-cut gears for the salt and helical gears for the street. High gear was a stout .86:1. Thirteen-inch Brembo disc brakes controlled deceleration; steering featured power-assisted rack-and-pinion. Fore and aft weight distribution was a near perfect 53/47.

Under the hood, Chisenhall cut no corners: A Donnie Anderson-built 705c.i. World Products Super Block V8, utilizing a dry-sump oil system, pumped out a robust 1,000 ponies at 5,600 rpm and 952 ft. lbs. of torque, sufficient oomph to make a mockery of the 200mph barrier. Oil coolers for the engine, transmission, and rearend, plus an oversize radiator – and a Vintage Air Monster electric fan – kept everything cool, whether speeding across the salt or cruising across Texas on Interstate 10. As Jack summed it up, “It was pretty much a race car that you could run on the street.” Construction took only eight months.

After an initial shakedown test at El Mirage dry lake – where the talcum-like dust actually helped to show air flow patterns – the car debuted at the 1994 Bonneville Speedweek. The coupe ran a blistering 219mph average and blew out the back door of the middle mile at a head-slapping 243mph. All the while, Chisenhall basked in the cool comfort of refrigerated air.

Despite the power and velocity, Chisenhall remembers the car was remarkably stable at speed. “Even at more than 200mph I could steer the car with only two fingers on the wheel, using only gentle corrections to keep it tracking down that black line.”

Since Chisenhall originally based the car on a NASCAR road race chassis, it was only natural that he test it out on the twisties. Another wheel-and-tire swap – sticky slicks! – and it was off to Circuit of the Americas in Austin, home of the U.S. Grand Prix Formula One race. “That was a blast,” he remembers. “It performed and handled very well – and wow did it pull out of the corners with that much torque!”

Today, the “Cool 200” coupe lives a more sedate life in the lobby of Vintage Air headquarters in San Antonio. Chisenhall still fires it up occasionally and it dazzles passengers brave enough to climb into the passenger seat.

There have been many fast hot rods, but Chisenhall’s coupe was unique. “These days, going 200 mph at Bonneville is more common than in the early days,” says automotive historian and publisher of TorqTalk.com, Tony Thacker. “But going 240mph with the air conditioning on, now that was special.”

“The car caught people’s imagination,” Jack explained. “Friends of mine are always being asked, ‘Does Jack still have the Studebaker?’ And that was 27 years ago! It also brought attention to Vintage Air, although that was incidental.

“But in the end, it’s just a fun car!”