Limefire Roadster – Dual Purpose Dynamo

The list of hot rod luminaries that roamed SoCal’s sunny landscape – many profiled in this column – helped define what we know today as “hot rod culture.” And every once in a while, a handful of such legends join forces to create a special vehicle, in this case Pete Chapouris’ electric-green Limefire ’32 Ford Highboy.

The influence of Mr. Chapouris stretched more than four decades, from Blair’s Speed Shop to Pete & Jake’s components, to SEMA to the phoenix-like rise of the So-Cal Speed Shop brand. His “California Kid” ’34 coupe became a star of the silver screen and magazine covers. Any definition of hot rodder would include his name.

Pete conceived the Limefire in late 1980s, a period unique in hot rod history. Billet had emerged from Boyd Coddington’s fertile mind; all manner of bits were being hewn from solid chunks of aluminum. The shape of hot rods had become sleeker and sleeker, door handles and hinges hidden, body seams filled, with more pastel colors than a spring Dolce & Gabbana catalog. The go-to moniker of such cars was “jellybean” or “Easter egg.”

It was during this stage that Chapouris decided to buck the trend. He imagined a “traditional” ’32 highboy, one that could double as a street-racing rocketship and on-track terror. Chapouris’ inspiration harkened back to a legendary 1960s-era hot rod, Tom McMullen’s radical street-and-strip ’32 roadster. He often told the tale of spotting McMullen’s Deuce at stop light. There it was in all its flamed glory – the blower, the big-and-littles, the American mags, the white tuck ’n’ roll, and its signature embellishment, a functional parachute adorning the deck lid. That memory was stuck with Pete for decades.

A quarter-century later, he decided to build his own version, first to show the billet-and-smoothie crowd that traditional hot rods still had a place, and second, to demonstrate how someone could assemble a hot rod from aftermarket parts, a prevalent trend by the late ’80s.

The project started by eschewing an original steel ’32 body for a fiberglass version from Wescott, another example of the thriving aftermarket. He also enlisted the support of B&M Automotive, which hoped to prove its performance products could excel on the interstate and on the track (emulating the dual success of the McMullen roadster). The entire project was chronicled by the late Gray Baskerville in Hot Rod magazine.

The project started by eschewing an original steel ’32 body for a fiberglass version from Wescott, another example of the thriving aftermarket. He also enlisted the support of B&M Automotive, which hoped to prove its performance products could excel on the interstate and on the track (emulating the dual success of the McMullen roadster). The entire project was chronicled by the late Gray Baskerville in Hot Rod magazine.

The selection of components melded traditional with modern. Chapouris chose a time-honored 350 Chevy small-block, bolstered with a 400 crank, pushing the displacement to 383c.i. B&M provided the water pump, camshaft, engine pulleys, transmission, and blower. This combination proved robust, pumping out a dyno-verified 495 ponies. The exhaust system featured hood-side-exit headers fabricated by old-school master craftsman Jim “Jake” Jacobs.

The chassis – put together by the esteemed Pete Eastwood – featured Just-A-Hobby frame rails and custom parts by Eastwood, including hairpins, pedal assembly, motor mounts, crossmembers, and driveshaft hoop. For the rear suspension, Eastwood used proven pieces from Pete & Jake’s. Finishing it off was a Halibrand quick-change that transferred oomph to 13-inch-wide Halibrand Sprint wheels, often wrapped in slicks.

Metal master Craig Naff (of CadZZilla fame) formed the car’s aluminum hood and four-piece hood sides. A Moon fuel tank sat in front of the grille, again mirroring McMullen.

Another aspect that echoed the McMullen roadster was its ability to change from a street to track setup. “We designed the car to be ‘transformer’ like,” explained Eastwood to the Gazette. “The interior was formed by aluminum panels with upholstery that could slip in and out, and a bench seat that could be swapped out for a race bucket, six-point roll bar, and competition seat belts.”

Whether set up for the street or track, the car was wickedly fast. “At the Bakersfield quarter-mile, with Chapouris behind the wheel, it ran 10.78 at 128 mph,” Eastwood recalled.

As for the dazzling lime-gold hue, legend has it that Chapouris’ father drove a late 1950s Buick, which had been repainted in a similar bright green color. Pete never forgot how much he admired it. Paint legend Stan Betz mixed up a color that matched Pete’s memory.

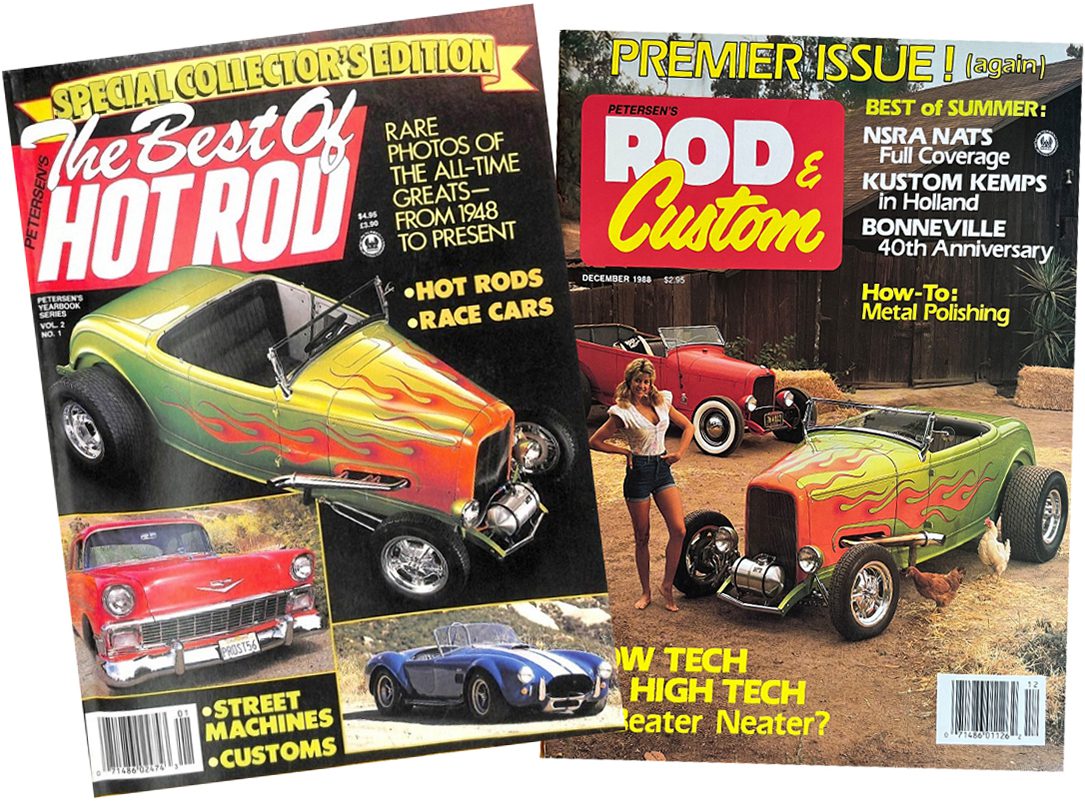

Upon completion, the Limefire roadster earned a blizzard of media coverage, including a cover and fold-out center spread in Hot Rod. It also appeared on the cover of a reborn Rod & Custom, with a photo shoot that recreated the legendary 1973 “Coupes are for Chickens” cover layout.

Upon completion, the Limefire roadster earned a blizzard of media coverage, including a cover and fold-out center spread in Hot Rod. It also appeared on the cover of a reborn Rod & Custom, with a photo shoot that recreated the legendary 1973 “Coupes are for Chickens” cover layout.

Chapouris. Jacobs. Naff. Eastwood. Betz. Baskerville. Wescott. A star-studded lineup that pooled their respective talents to create a memorable and influential hot rod, honoring another memorable and influential hot rod, the Tom McMullen deuce. Oh, and McMullen is a legend, too.

Sir Isaac Newton (all-time legend) once said his discoveries were built on the shoulders of giants. Hot rods work the same way. Every shade-tree mechanic and garage warrior are influenced by the craftsmen who showed the way. And there is no better example of this principle than the Limefire roadster.