Whatever Happened to Mickey Thompson’s Dragster – The Harvey Aluminum Special?

The Harvey Aluminum Special – What happened to this special Mickey Thompson Dragster?

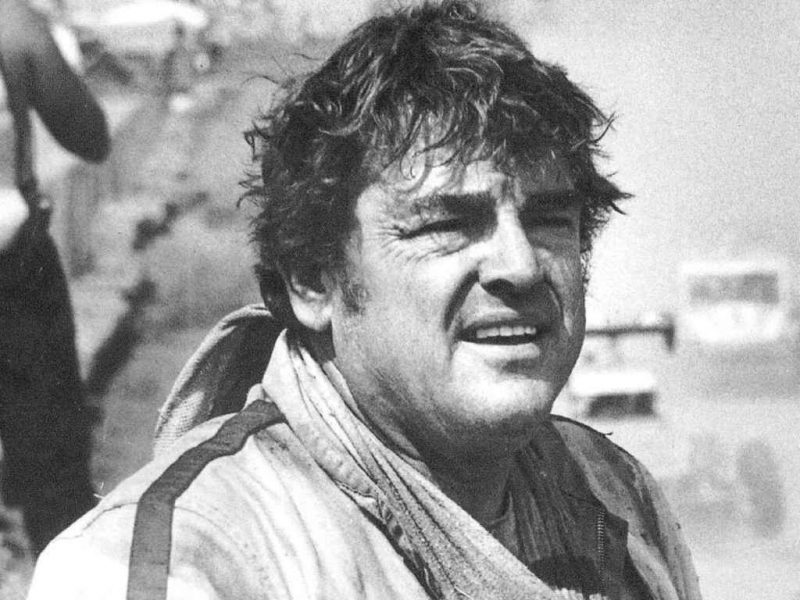

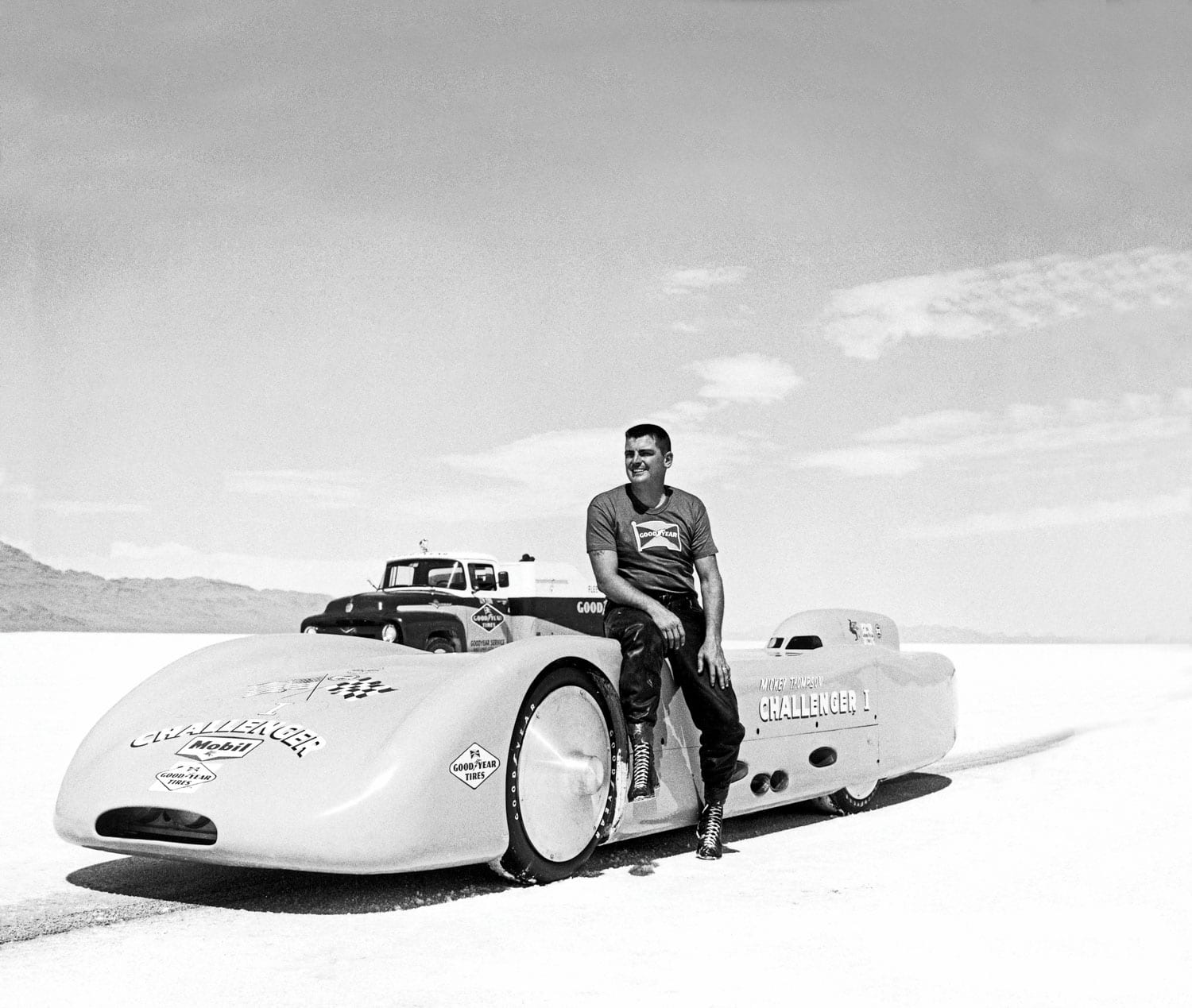

While we all think we work hard, the late Mickey Thompson worked harder. By day he ran M/T Enterprises and Lions Drag Strip and at night he did a shift at the Los Angeles Times. Meanwhile, he built an unimaginable array of very fast cars. In the early 1960s Mickey had more balls in the air than the Cirque de Soleil: He was breaking speed records at Bonneville, Indy car racing and drag racing—all at a harder pace than anyone can imagine and all with astonishingly successful results. However, there was a dragster that did not garner much attention, at least not in the US.

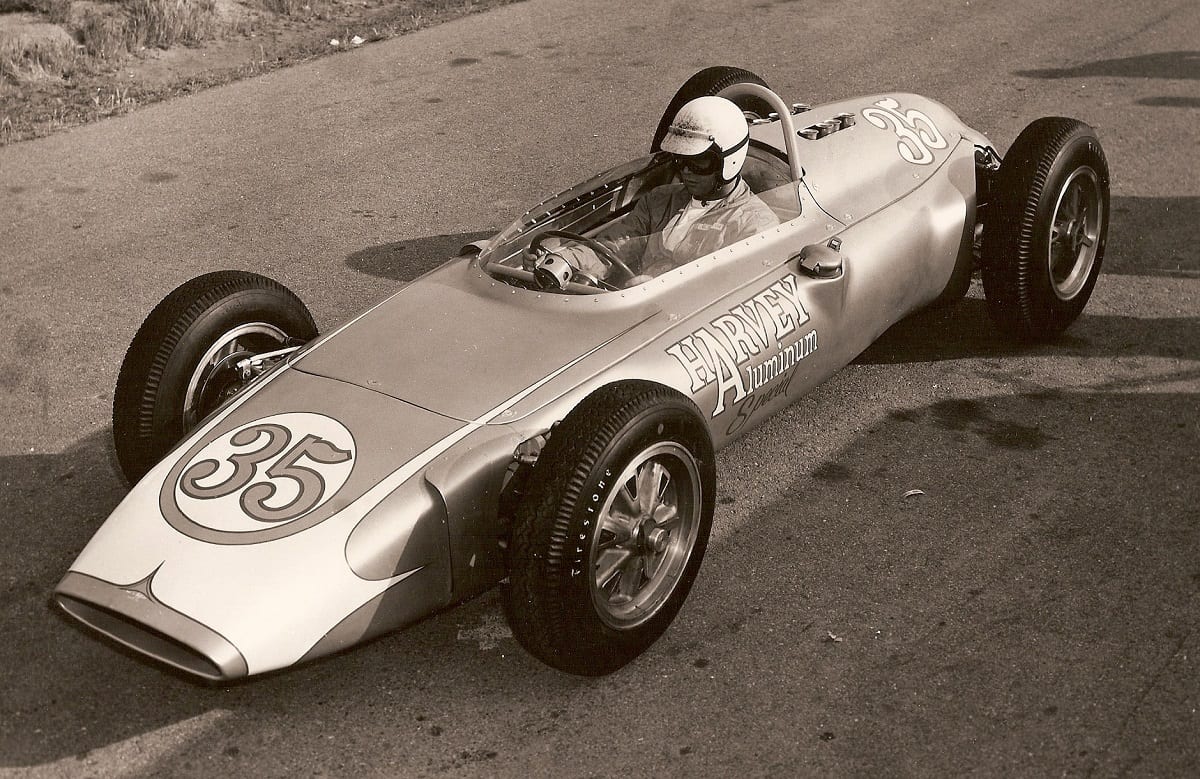

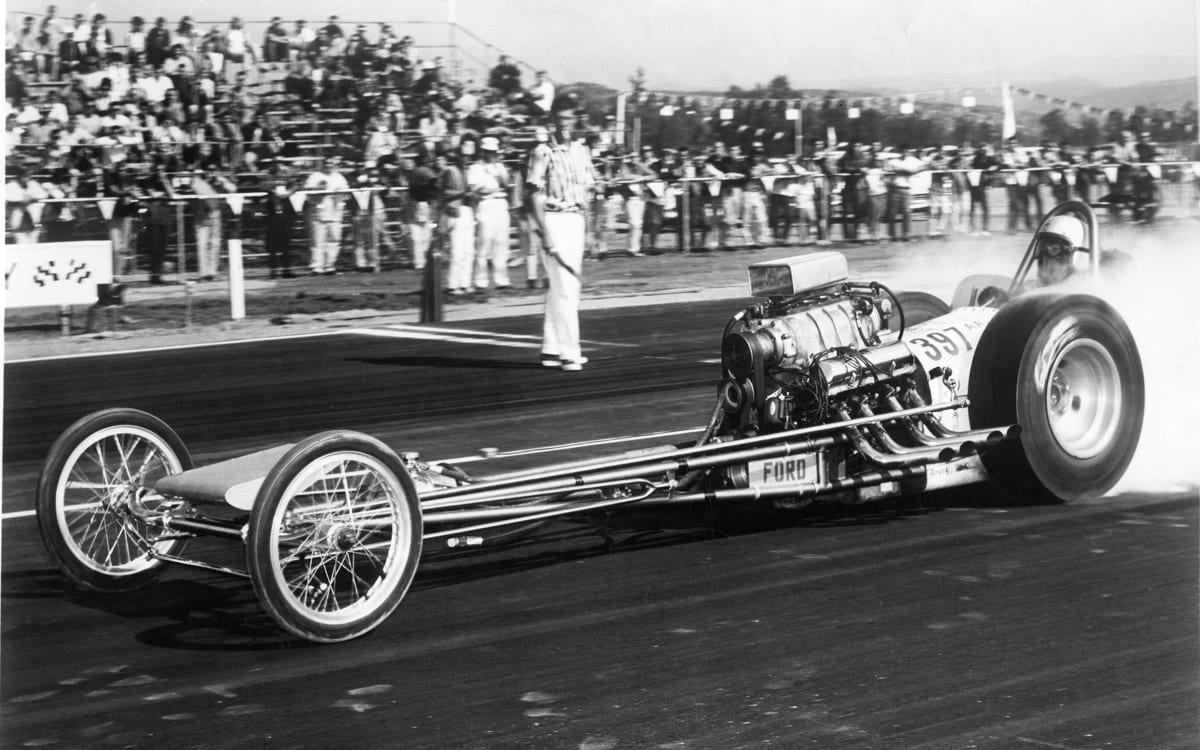

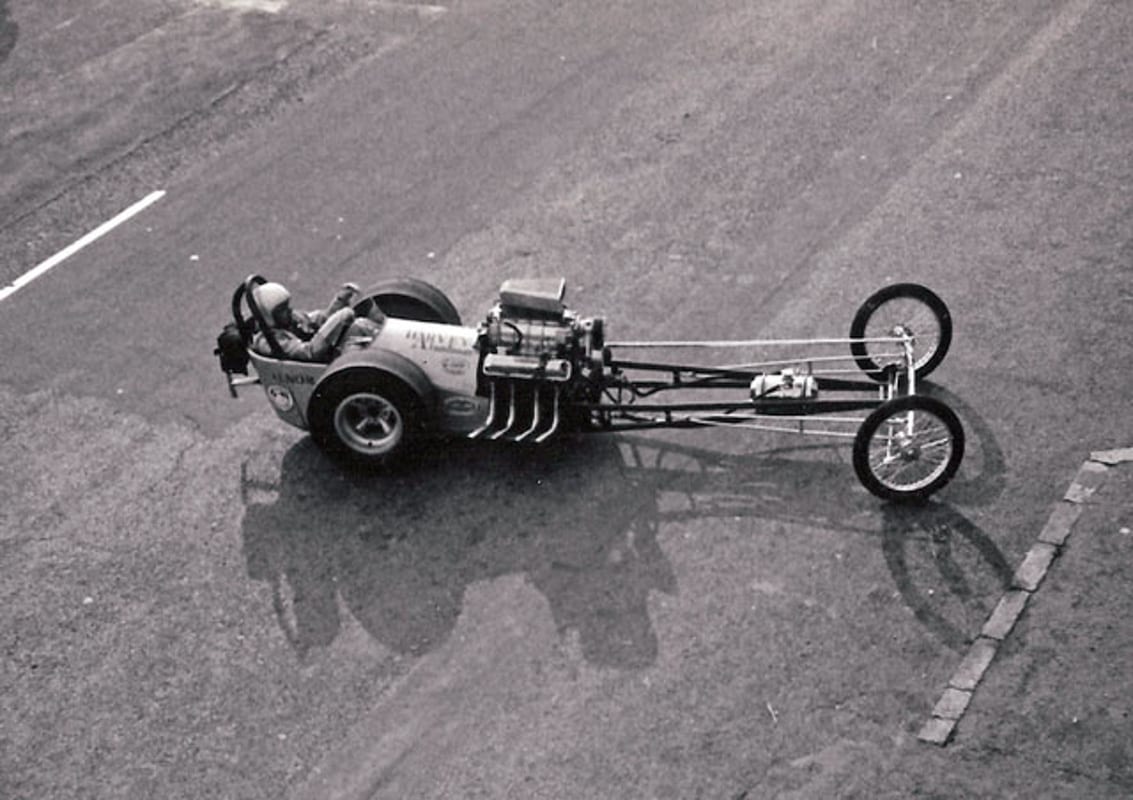

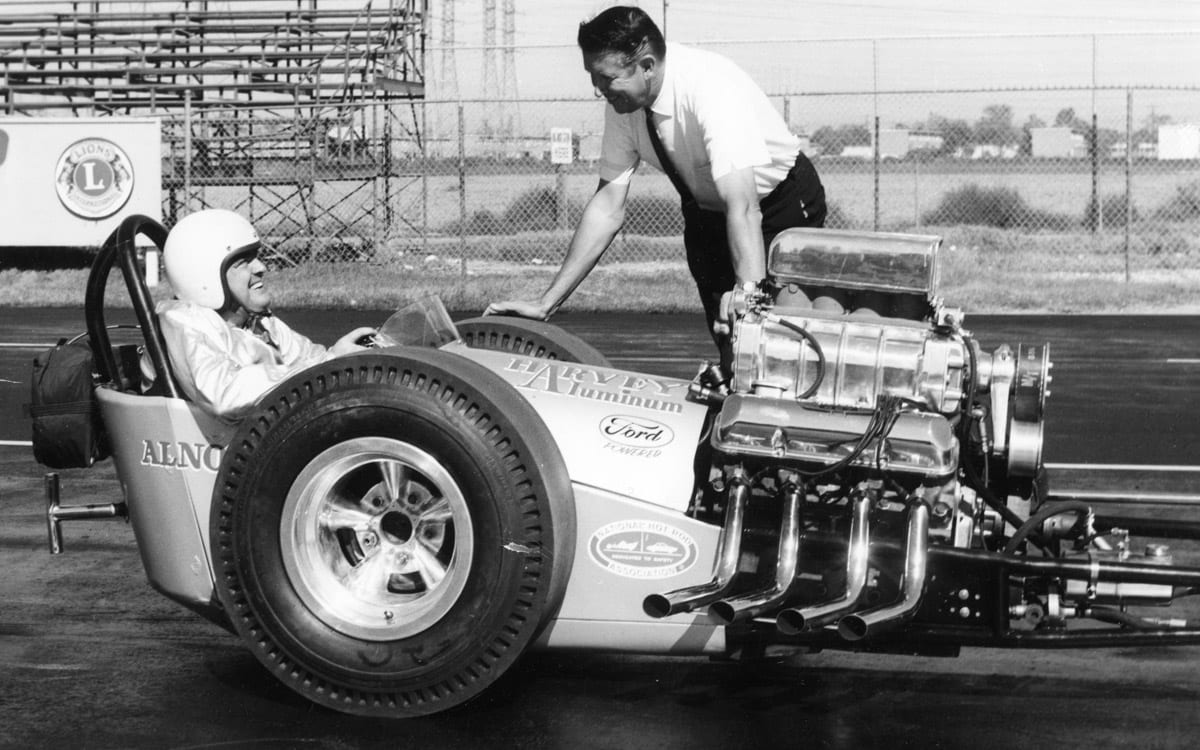

Unlike most of M/T’s previous rails that featured Dragmaster frames, the frame for the Harvey Aluminum Special (HAS) was distinctly different. It was the shape of things to come, the epitome of the slingshot with a long tapered frame, a big 4-bolt Ford 427 Wedge tilted forward and M/T sitting low with his legs up over the Olds rear end.

At first, we were led to believe by Tom Madigan’s book Fuel & Guts, that Roger Wolford built it. Roger worked for Scotty Fenn, the first commercial chassis builder. Later, in 1962, he worked and drove for Mickey Thompson. However, we spoke to Roger and he said the frame was built at Tommy Ivo’s shop.

We called ‘TV Tommy’ and he confirmed that the chassis was built in his Speed Specialties shop in Burbank where Rod Peppmuller was fabricating. Tommy said, “We made 14 cars and when Mickey wanted one I was so star struck I pushed him to the head of the line. Then he let Jack Chrisman drive the first time out at Lions and he crashed.”

NHRA Museum curator Greg Sharp was there that day, Sept 15, 1962 and commented, “Jack pulled a wheelie, turned left and hit a telephone pole laying in front of the tower. Jack was knocked out and the motor was still running so Ted Cyr jumped up and pulled the plug leads. It was exciting. I was only 17 years old.”

Ivo picks up the story saying, “ The car came back to my shop and I annoyed all my customers again by putting Mickey back at the head of the line again. We used what we could from the wreck.” I asked about the Pontiac motor and the dark blue metallic paint and Tommy said, “Between the birth of the car in 1962 and the trip to England in ’63 M/T had a lot of time to change motors, paint, etc. He’d change sponsors faster than I changed underwear.” Obviously, Mickey was using the car as a test bed for his growing line of speed equipment and besides, GM chairman Fred Donner had pulled the plug on all GM racing in 1963. Hence M/T’s switch to Ford.

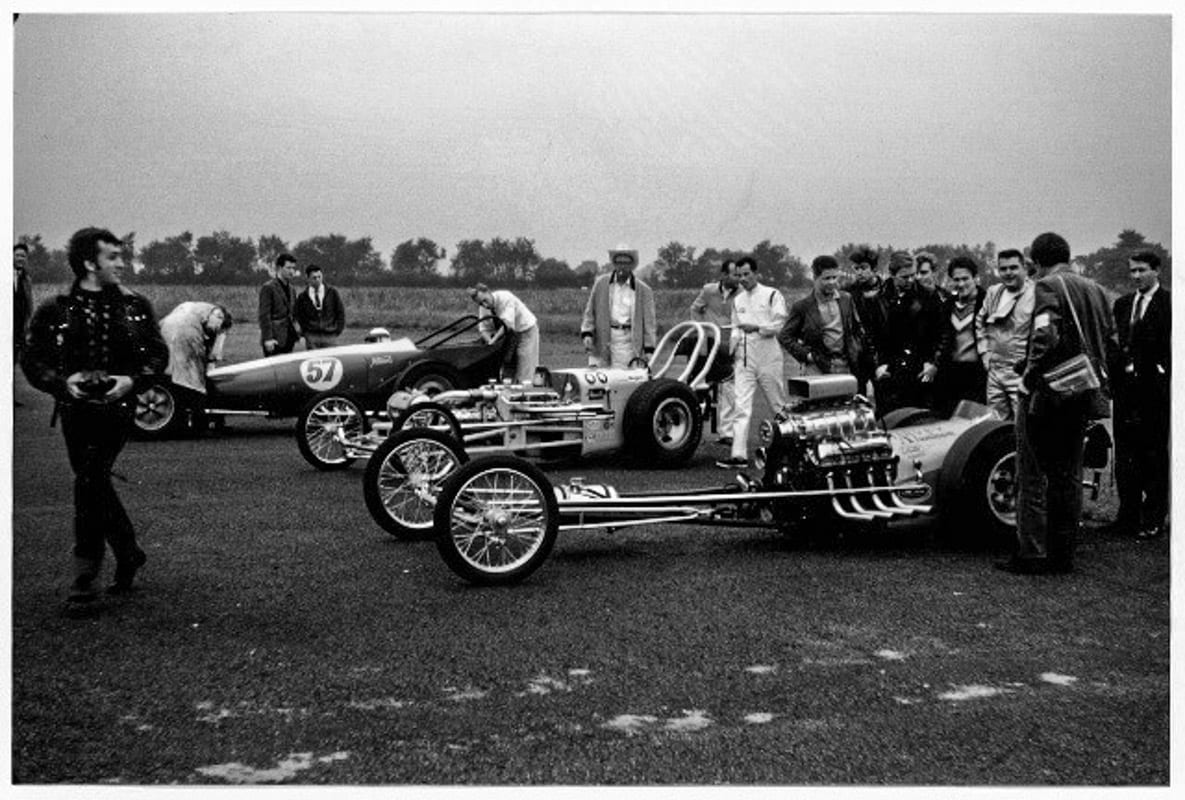

Meanwhile, that same year, having read about Sydney Allard’s efforts to introduce drag racing to England, Dante Duce called Sydney and Dean Moon and proposed taking the Mooneyes Dragster to England for a series of exhibition runs against the Allard Chrysler dragster. The industry was all for it. SEMA put up an impressive trophy, Mobil and Revell came on board as sponsors (those were the days) and Sydney Allard agreed to cover the costs of shipping, hotels, etc., (those were the days).

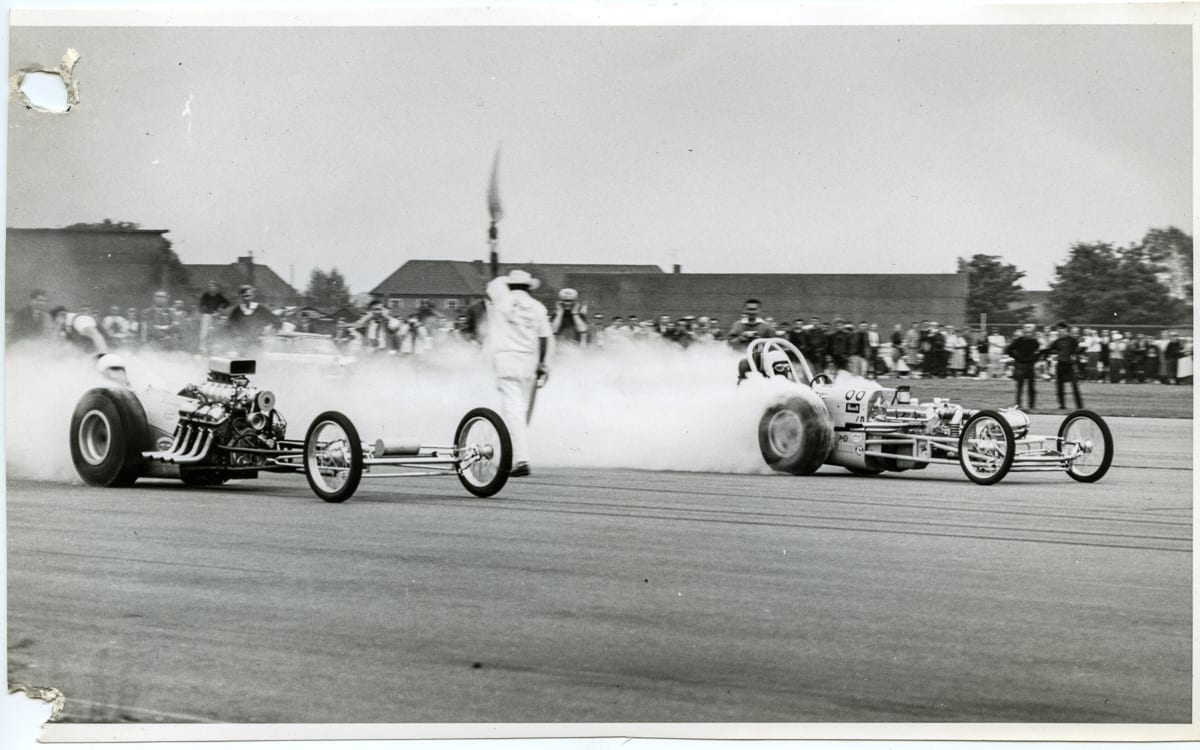

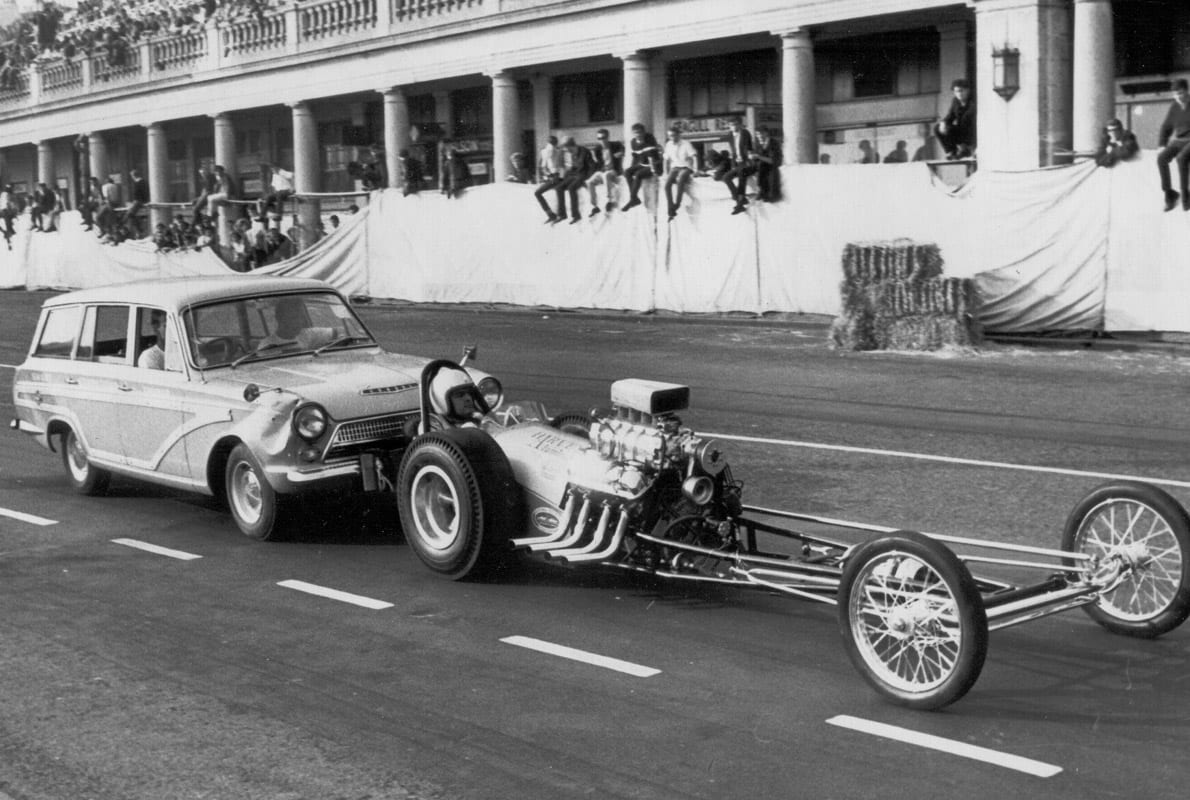

The planned trip generated a lot of publicity on both sides of the pond and never one to miss a PR opportunity Mickey jumped on board. Late to the party, Mickey missed the boat but somehow persuaded the USAF to fly his car to England. Unfortunately, he missed the first event at Silverstone. However, he was there in time to run at the 58th Brighton Speed Trials. Organized by the Brighton & Hove Motor Club and held on Madeira Drive, a sea-front street alongside the beach on the south coast of England, the Trials was a side-by-side sprint and not a drag race. The cars competed against the clock not each other. Also, the Royal Automobile Club (RAC), the sanctioning body for all UK motorsports at the time, decreed single runs only because the dragsters had no front brakes.

To prove the RAC’s fears well founded, both guys put on spectacular smokey displays: M/T’s exhaust apparently setting the straw bales on fire. He also pulled a strong wheelie that was good enough to feature on the 1964 program cover. The Brits loved it. You can even watch some short footage of the event here.

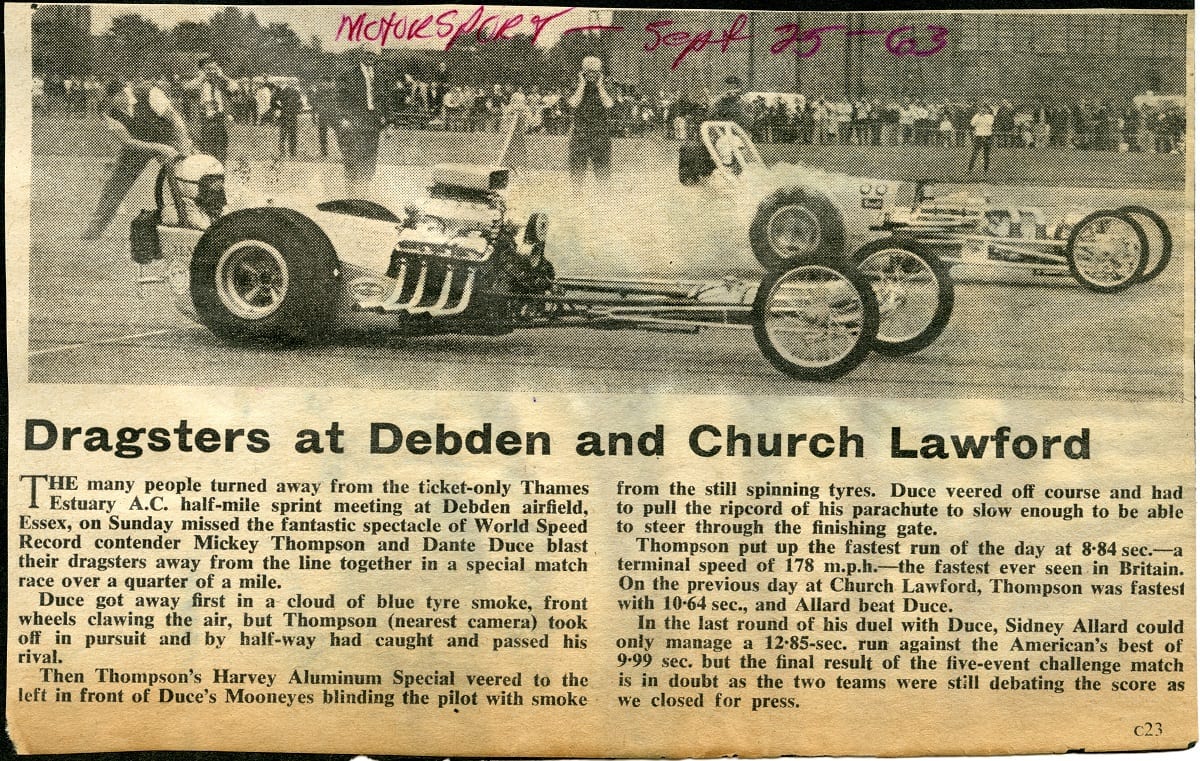

From Brighton the action moved north to a little publicized event at an airfield at Church Lawford, Warwickshire, where M/T laid down a 10.674 at 141 mph—fast for the extremely rough course. Then it was on to the final at RAF Debden, Essex. Although not billed as a spectator event (what were those Brits thinking?) an estimated 5,000 sneaked in to watch the final run flagged off by Dean Moon hisself.

Thompson, running nitro won of course, with a speed of 178 mph and an E.T. of 9.21. However, his best time was 8.84 seconds. Here is what it looked like!

The whole series, though poorly promoted in best Brit fashion of the day, generated lots of publicity and British drag racing was off to a flying start—not so M/T’s rail. For some reason the car could not leave the same way it arrived and it was therefore left in England to supposedly be used by Ford for dealer and other promotional purposes.

The car just kinda disappeared, as they did, but it reappeared complete but in poor condition, according to David Withers, in June 1965 at a Perkins Engines “Sports and Family Day.” The following year it reemerged repainted gold and minus the M/T graphics as the Golden Hind. Indeed, I took a very poor snap of it at Santa Pod Raceway in 1966.

And here the reports gets cloudier and the true fate of the Harvey Aluminum Special is the subject of much debate on the Internet. The rumor for many years was that the Hind was subsequently rebuilt as the Commuter—probably Britain’s most famous dragster. Others deny that saying that it was merely a “blueprint.” There’s probably truth in both answers. To get a clearer picture we called Antony Billinton of UK fuel supplier G-Max who’s father Peter was intimately involved in the creation of Commuter with Densham and Bob Phelps and his son Roy.

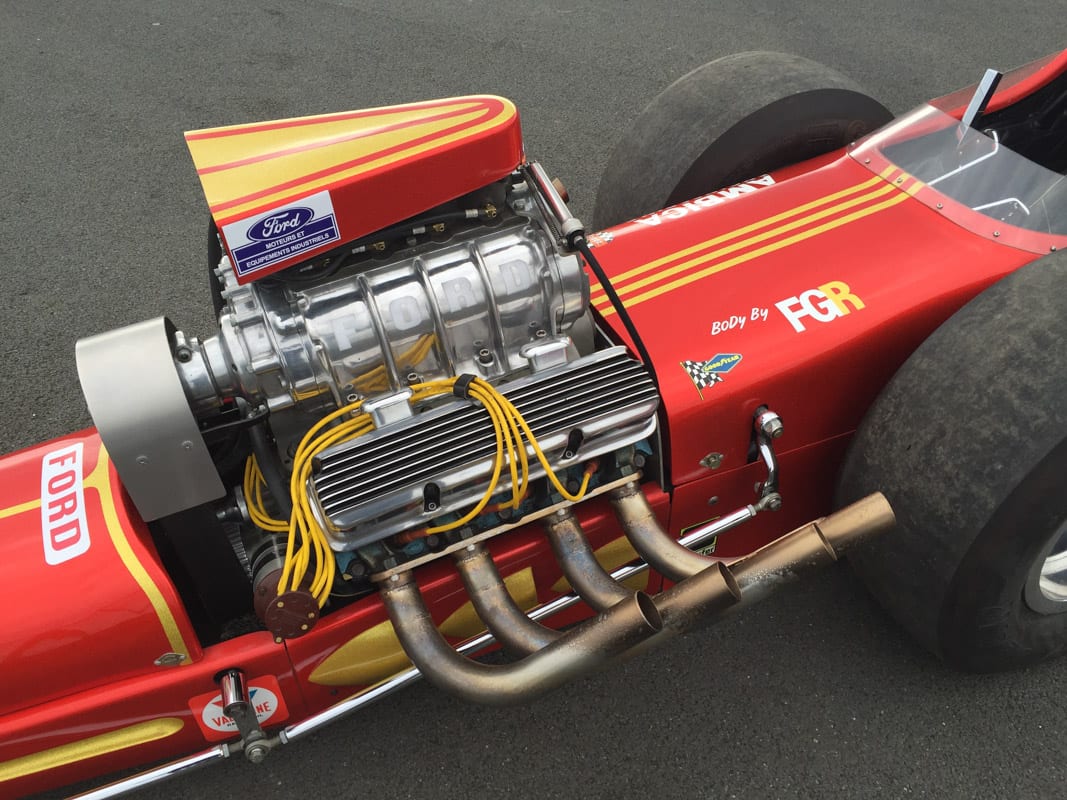

“The Commuter was inspired by Mickey Thompson’s Harvey Aluminum Special and shared a similar chassis and Ford motivation—a 427 Wedge. Unlike the HAS car, however, The Commuter was clothed in a body hand-built by Bob Phelps’ Fibreglass Repairs (FGR) shop, styled along the lines of the infamous Stellings & Hampshire Red Stamp Special AA/FD built by Kent Fuller.”

Antony, went on to say, “The chassis was fashioned from high-tensile steel, again by FGR in Bromley, and initially measured 144 inches in length. The narrowed 1955 Oldsmobile rear axle was equipped with 10.5x15in American Racing magnesium wheels and M&H slicks. At the front, 17-inch diameter Borranis with Goodyear 2.25x17in tires were hung either side of a dropped tube axle.

“The engine was undoubtedly the most unique aspect of The Commuter at the time, and remains so to this day, thanks to its extreme rarity. Apparently only a thousand or so, 4-bolt mains, Ford 427 Wedge engines were built, and Mickey Thompson was the man with the reputation for making them perform on the drag strip. The 1965 example used in The Commuter was assembled using Mickey Thompson know-how and delivered between 1500 and 2000 hp. It featured his own brand of connecting rods and slipper-type pistons, together with an Iskenderian roller camshaft, GMC 6-71 blower, Cragar inlet manifold and Hilborn four-port fuel injection.”

I think therein lay the clues that while Commuter was not entirely the HAS, a fair amount was. For example, HAS had chrome steel front rims not aluminum Borranis. The steering and aspects of the frame were different—four links instead of wishbones—but it’s my guess that the mechanicals were the same. I don’t believe that at that time, the Brits had the wherewithal to locate another 427 Wedge when so few were available. But, that’s only my guess. However, Anthony did point out that those engines were available in the UK because of local Cobra production. Incidentally, Antony still owns the original HAS/GH body panels. How cool that he saved them all this time.

Commuter debuted at the London Racing Car Show in January 1967 and, of course, went on to help establish drag racing not only in England but also across Europe. Later that year Commuter also set a number of F.I.A. land speed records which, at the time, had to be set in both directions within one hour.

In 1970, the team returned to Elvington, Yorkshire to break Sir Malcolm Campbell’s unbroken 1927 record for the flying 500 meters and kilometer records of 174.883 mph. With a custom radiator packed into the nose, a larger fuel tank and a dose of nitro Commuter’s two-way average was 207.6 mph. According to Antony, this record still stands. Commuter was also the first dragster to break 200 mph in the quarter in England.

After a glorious career in the hands of Densham, Commuter again went into storage until Antony restored the car to its 1967 Metalflake red glory. It debuted in 1996 as part of Santa Pod’s 30th Anniversary celebrations.

But wait, there’s more. While researching this story NHRA Museum curator Greg Sharp and myself kept finding pictures of another M/T dragster that looked a whole lot like the HAS car—but not quite. Numbered 397, this FED was depicted throughout the Petersen publication, Mickey Thompson’s Performance Handbook, as a, “Test car on which all the new M/T Ford speed equipment received a thorough shake-down on the drag strip before being released for sale.”

We know the 397 car is not the HAS because we have shots and records of it racing at the grand opening of the San Diego Raceway at Ramona, near San Diego in November ’63. The newspaper report of the event says, “The Los Angles owned Waterman, Goodsell and Clearspark supercharged Chrysler out sped Mickey Thompson’s supercharged fuel-burning Ford-powered dragster in two straight races. Thompson was breaking in a new engine.”

What happened to 397 is another story but I think we can be certain that the Harvey Aluminum Special that went to England in 1963 became the Golden Hind and begat the Commuter.