Art Chrisman: Drag Racing’s Do-It-All Guy

Some guys can build an engine. Others can fab up a chassis. Tuning is a skill in which others excel. And who doesn’t think he can drive? Finding someone who can do it all and do it with panache and performance, well, that as rare as a trustworthy Facebook post. Fortunately, the world of drag racing can claim one such individual, the legendary Art Chrisman. Chrisman, who passed away in 2016 at age 86, was a Swiss Army knife of quarter-mile talent.

Some guys can build an engine. Others can fab up a chassis. Tuning is a skill in which others excel. And who doesn’t think he can drive? Finding someone who can do it all and do it with panache and performance, well, that as rare as a trustworthy Facebook post. Fortunately, the world of drag racing can claim one such individual, the legendary Art Chrisman. Chrisman, who passed away in 2016 at age 86, was a Swiss Army knife of quarter-mile talent.

Art Chrisman hailed from Sulphur Springs, Arkansas, born into a family whose life revolved around cars; his father owned a garage and kept all manner of autos and tractors fulfilling their mission. Coming of age in such an environment imbued in young Art the desire and skills to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Those steps first led Art to southern California during WWII, where the family relocated so the elder Chrisman could help the war effort by building Liberty ships at the San Pedro shipyards. Meanwhile, Art’s academic focus at Compton High School was distracted by the emerging hot rod scene rumbling outside his classroom  window. It wasn’t long before he joined in the fun, drafting the family ’36 Ford four-door sedan into race duty. He pushed the family wheels to 109mph at El Mirage and 90mph at Santa Ana dragstrip. Art’s future was slowly coming into focus.

window. It wasn’t long before he joined in the fun, drafting the family ’36 Ford four-door sedan into race duty. He pushed the family wheels to 109mph at El Mirage and 90mph at Santa Ana dragstrip. Art’s future was slowly coming into focus.

It was perhaps the last thing that happened slowly for Chrisman. He and his brother Lloyd ditched the ’36 for a ’34 Ford coupe. They tweaked the flathead V8 and soon topped 140mph at the lakes in 1950.

Art Chrisman’s obvious natural talent caught the attention of renowned camshaft impresario Chet Herbert. Together they put together a Chrysler Hemi-powered streamliner – tagged the Beast III – for Bonneville. When the assigned driver was a no-show, Chrisman jumped behind the wheel and set a new class record of 235mph!

Next up, Chrisman developed a ’30 Ford coupe for the lakes and the salt. The car went through various iterations, eventually running a mid-engined alky-injected Hemi. Aided by an aero-shaped nose and a top-chopped so severely a #10 envelope would be a squeeze, the car set a Class D record of 196mph. This car went on to have a crazy history – modified by George Barris for television, then gussied up for a turn as a show car, before finally ending up back in Chrisman’s hands for a full restoration.

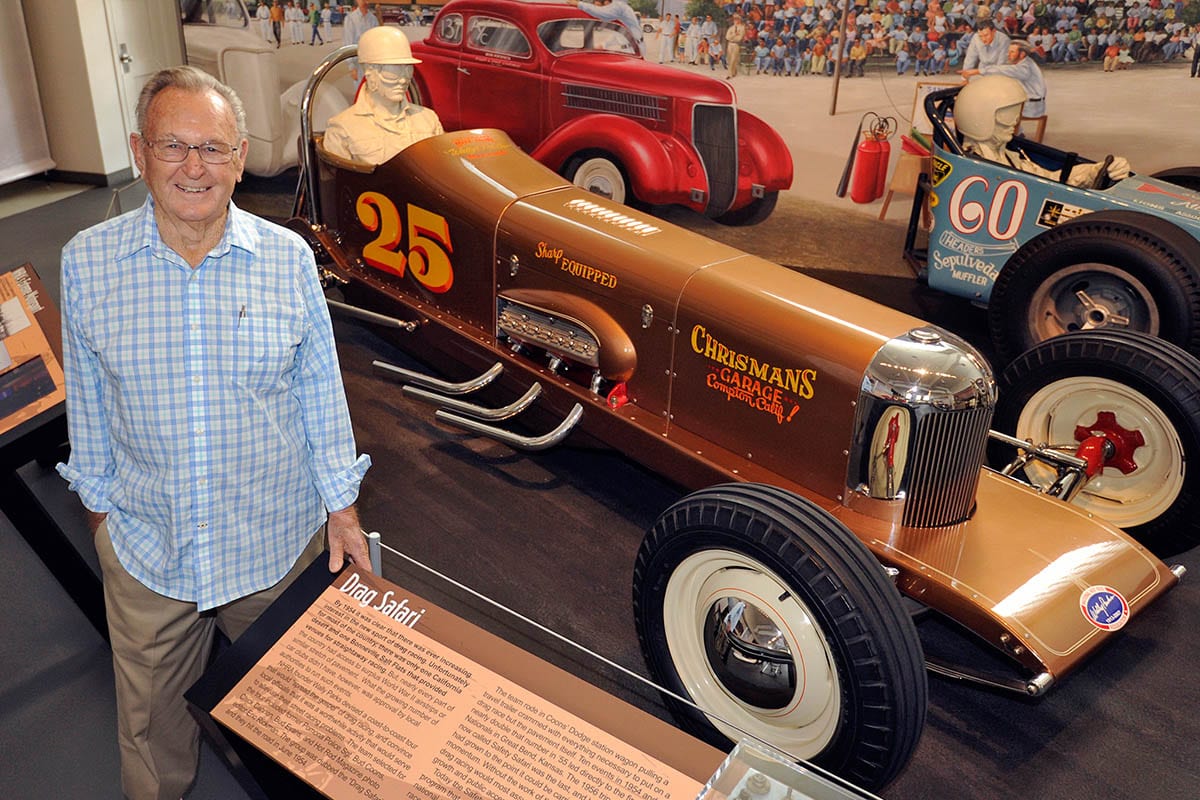

At this point, Chrisman migrated to the quarter mile, where he rewrote the record books with two dragsters for which he is most famous. First up, the legendary No. 25 dragster. A converted dry-lakes modified car whose palmarès date to the 1930s, in 1953 it was the first machine to exceed 140mph – earning a cover appearance on Hot Rod in the process. Moreover, it owned the distinction of making the first-ever pass at the inaugural NHRA Nationals at Great Bend, Kansas, in 1955.

Eventually, No. 25 was eclipsed by the newfangled slingshot dragsters. But not for long. Chrisman emerged from his workshop with a dazzling cigar-shaped dragster called The Hustler. It was as fast as it was beautiful, a high-performance sculpture of sorts that earned Best Engineered honors the 1958 NHRA Nationals as well as a cover kudos on the January 1959 Hot Rod.

On the track The Hustler was a force that few could reckon with: It bolted down the Riverside Raceway tarmac at 181.81mph – the first car to topple the 180mph barrier. Art and his Hustler also raced home with the Top Eliminator trophy at the first Bakersfield U.S. Fuel and Gas Championships.

By the early 1960s, motorsports was thriving and corporations were looking to cash in on its popularity. In 1962, Chrisman accepted a position with Ford’s Autolite Spark Plug Division as a combination ambassador and speed-savvy savant. He crisscrossed the country sharing his know-how with all types of racers – NASCAR, USAC Indy cars, NHRA drag racing, and Bonneville. Remember, during this era reading spark plugs was the most critical diagnostic key to engine tuning, and Chrisman was the ace of the electrode.

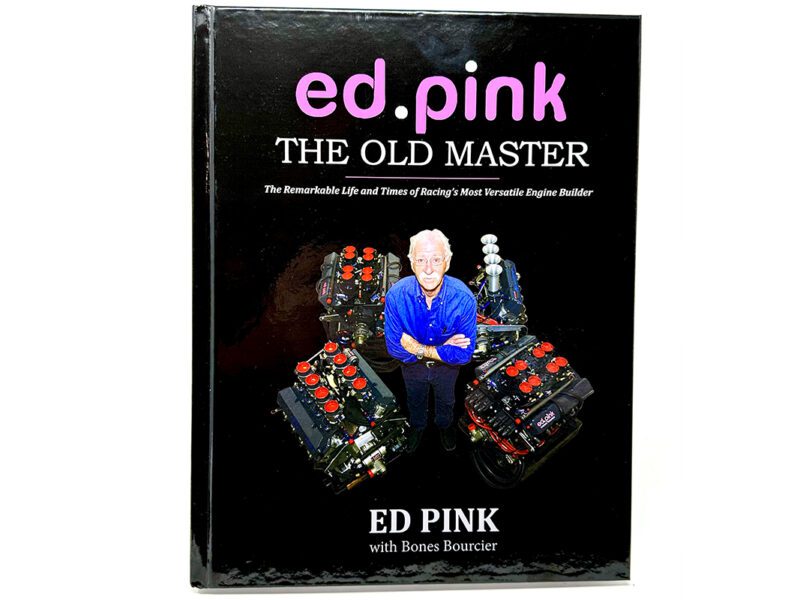

Following a decade of plugging away for Autolite, in 1973 Art Chrisman hooked up with famed engine builder (and fellow Goodguys Hot Rod Legend) Ed Pink, overseeing Pink’s dyno operation. This included R&D contracts with TRW pistons and SEMA.

In the early-’80s he partnered with his son, Mike, and opened Chrisman’s Auto Rod Specialties (CARS) in Santa Ana, a return to his roots. The  father-son duo cranked out a host of top-flight race cars and hot rods. Of course, his engine expertise was also in demand, and Chrisman-crafted powerplants found their way into Jamie Musselman’s 1982 America’s Most Beautiful Roadster, the restored Greer, Black and Prudhomme dragster; Dennis Varni’s 1992 AMBR winner; and ZZ Top’s Cadzzilla, to name but a few.

father-son duo cranked out a host of top-flight race cars and hot rods. Of course, his engine expertise was also in demand, and Chrisman-crafted powerplants found their way into Jamie Musselman’s 1982 America’s Most Beautiful Roadster, the restored Greer, Black and Prudhomme dragster; Dennis Varni’s 1992 AMBR winner; and ZZ Top’s Cadzzilla, to name but a few.

All of Art Chrisman’s accomplishments, on the track and in the shop, did not go unnoticed. He earned membership in the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame, the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America, the Dry Lakes Racing Hall of Fame, and the Grand National Roadster Show Hall of Fame. He also was honored with the Robert E. Petersen Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2001, he ranked No. 29 on the NHRA Top 50 Drivers list.

The Chrisman family legacy will live on. He was survived by Dorothy, his wife of more than 60 years, son Mike, plus a passel of grandchildren and two great grandchildren. But Chrisman’s legacy as a racer and innovator will outlive us all.