Harry Miller – Racing’s Most Influential Pioneer

For this month’s Legends column, our editors aimed our way-back machine to the early days of the 20th Century, a time when automobiles — and motor racing — were in their infancy. A time when a high-school dropout from a small Midwestern town would go on to change the face of motor racing.

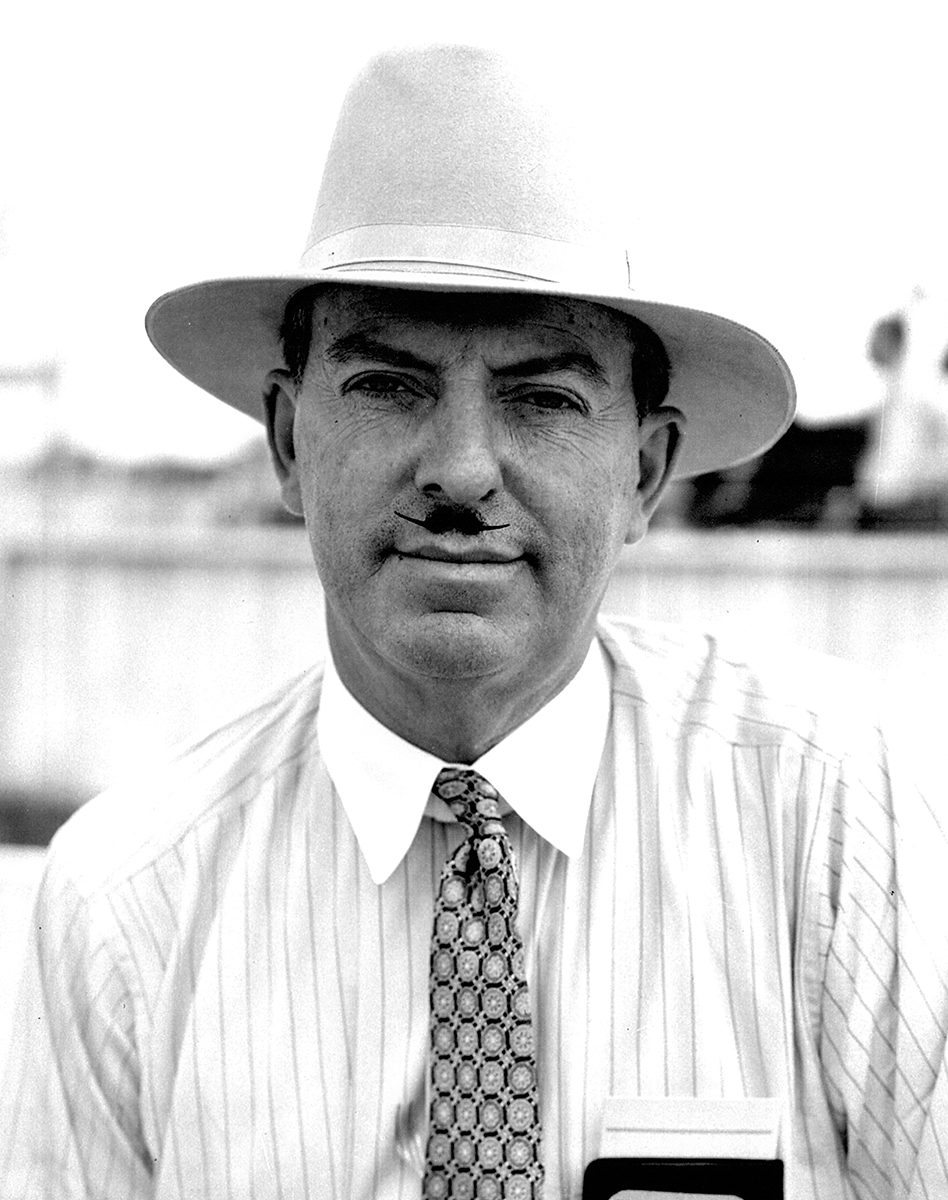

That dropout was Harry Arminius Miller, born December 9, 1875, in Menomonie, Wisconsin. That’s right, 1875 — nearly three decades before the automobile would transform the world.

As a teen, Harry Miller wasn’t the type of adolescent who could be confined to a classroom, so he withdrew from school and caught on at a local machine shop, which supplied parts to fledgling automakers. One client was Ransom E. Olds (who would later add “mobile” to his surname). Miller also couldn’t be confined to the Midwest: At age 19, he moved to Los Angeles.

As a teen, Harry Miller wasn’t the type of adolescent who could be confined to a classroom, so he withdrew from school and caught on at a local machine shop, which supplied parts to fledgling automakers. One client was Ransom E. Olds (who would later add “mobile” to his surname). Miller also couldn’t be confined to the Midwest: At age 19, he moved to Los Angeles.

Once in SoCal, he landed employment as a foundry foreman. But in his off-hours, he worked on designing an improved carburetor. Using a used lathe and drill press, he began producing his original design, aided in large part by his development of a new metal alloy, a blend of aluminum, nickel, and copper. He called it Alloyanum.

In 1912, Miller’s carburetors — for which he secured several patents — became must-have for serious racers; cars running Miller carbs dominated racing across the country.

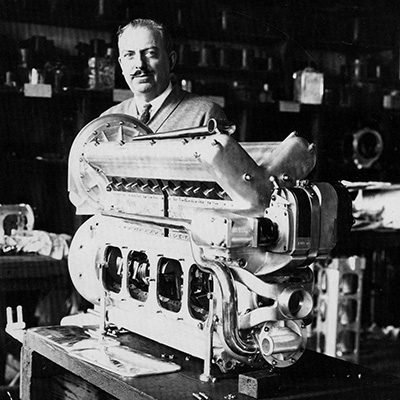

In 1915, Miller’s Master Carburetor Company became Harry A. Miller Manufacturing Co., with Harry expanding his repertoire to include the design and assembly of complete racing engines. This included a redesign of the novel Peugeot double-overhead-cam, four-valve engines, which had won at Indianapolis in 1913. This four-cylinder design later evolved into the Offy.

By 1921, Miller was also constructing complete racing cars, starting with the Miller 183, utilizing yet another Miller engine, a 183-inch twin-cam, 32-valve straight eight. Only a handful of 183 cars were built, but the powerplant cemented Miller’s reputation as “the guy” by powering Jimmy Murphy to the Indy 500 winner’s circle in 1922.

When Indy adopted a new 122c.i. formula in 1922, Miller adapted quickly, developing the Miller 122 chassis and engine; the engine was based on the 183, only with less displacement and a two-valve hemispheric head. Its dominance was unprecedented: In 1923, 46 percent of the Indy starting field was Millers, by 1925 it was 73 percent.

Miller continued adding upgrades to the 122, ushering in supercharging, front-wheel drive, aerodynamics (enclosed front axle) and more. When Indy changed its formula again in 1926, Miller designed yet another engine and race car, the Miller 91, offering both rear- and front-wheel drive configurations. Supremacy continued, scoring a series of international speed records and more brickyard mastery — from 1926 to 1929, three-quarters of the Indy starting field were Millers.

Miller retired from his business in late 1929. Weeks later the stock market crashed, sending the U.S. economy in a tailspin. Undeterred, a year later he unretired and launched a new engineering company. Sadly, the economic downturn had sucked the air — and money — out of motorsports. Despite Miller’s experience, winning record, and technical acumen, the business never gained traction. Within three years Miller was forced into bankruptcy.

Miller retired from his business in late 1929. Weeks later the stock market crashed, sending the U.S. economy in a tailspin. Undeterred, a year later he unretired and launched a new engineering company. Sadly, the economic downturn had sucked the air — and money — out of motorsports. Despite Miller’s experience, winning record, and technical acumen, the business never gained traction. Within three years Miller was forced into bankruptcy.

Down but not out, Miller retreated to New York, where he met a racing enthusiast who would later gain fame as a boutique automaker — Preston Tucker. Tucker was keen on entering a car in the Indy 500, and he believed a stock-block engine in a modern racing chassis — such as one from Miller — might achieve brickyard glory. In 1935, Tucker sold Ford Motor Company on the concept and recruited Miller to design and build ten cars. The budget was a $75,000 ($1.6 million today). Unfortunately, the project was beset with a tight timeframe, logistical problems, and inadequate testing.

The result was a huge let-down: Ten cars were entered; four qualified; all four DNF’d. The alliance between Ford and Miller was over, but the cars themselves? Simply stunning, still recognized today as one the most beautiful American racing cars ever created.

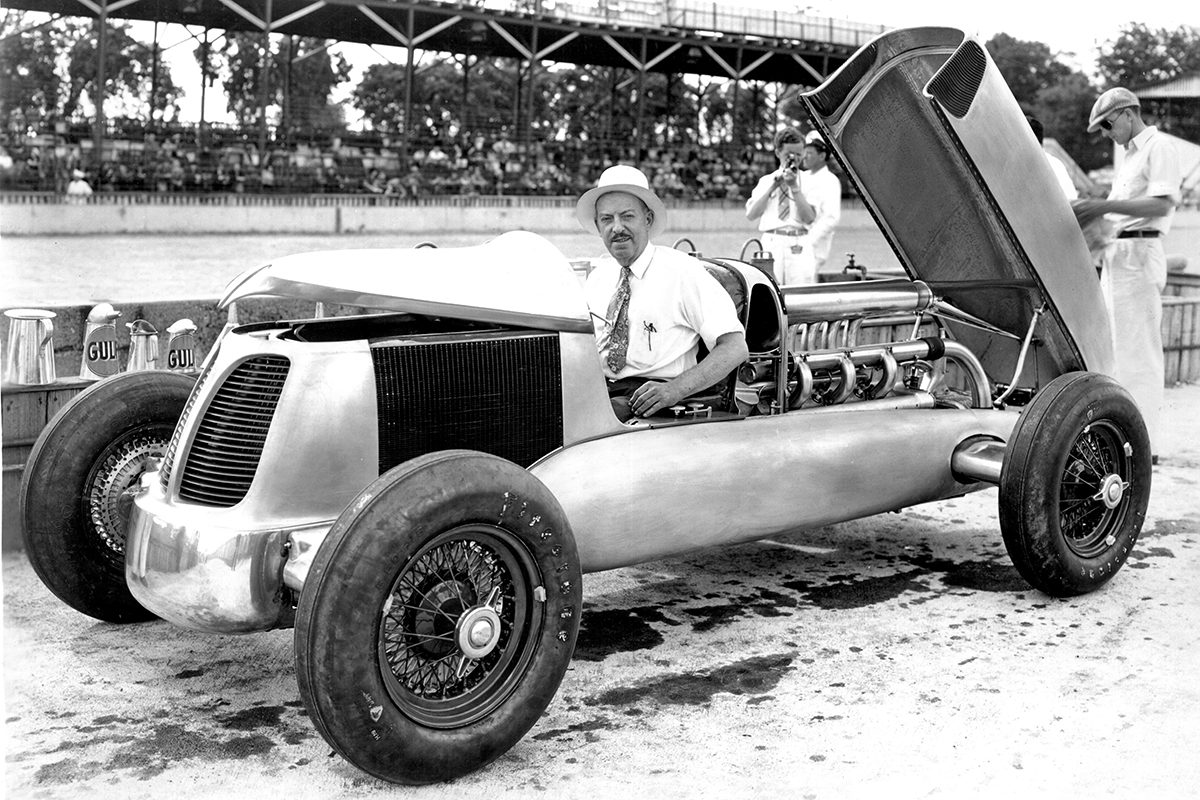

But Miller wasn’t done yet. He struck up another corporate partnership, this time with Gulf Oil Company. The petri-giant commissioned Miller to create a car that could complete at Indy and on the international Grand Prix circuit. By now, Miller was 63, and in poor health. He knew this might be the last significant project of his career. Again, his innovative and intricate machines were rushed to completion. They failed to qualify for the 1938 Indy race.

Miller’s health continued to decline and on May 3, 1943, he died from a heart attack. Tucker paid for his funeral expenses.

Miller’s contribution to motorsports did not go unnoticed. He was inducted into the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame, the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America, and the Automotive Hall of Fame. In 1995, the Harry Miller Club was founded to recognize his distinguished career.

All told, Miller’s cars won the Indianapolis 500 10 times and machines powered by Miller or Miller-based Offenhauser engines won another 29 times, plus additional 43 national championships.

Author Griffith Borgeson summed up Miller best in his definitive biography, “Miller”: “Harry Miller was, quite simply, the greatest creative figure in the history of the American racing car.”