Art Morrison Enterprises – Venture and gain

Even though Art Morrison Enterprises has been offering performance suspension for decades, they’re continuously pushing the envelope and growing at a record pace. They’re movin’ on up you could say.

Let’s face it though, there’s probably nothing more boring than a company’s announcement that it moved into a new building. As someone who gets paid to write, I’m here to tell you that not even the business owners want to read those things. They just want the rest of us to read them. And be impressed.

That said, we’re pleased to announce that Art Morrison Enterprises just moved into three new buildings.

Okay, so we kid. But there’s actually something interesting to take away from Art Morrison Enterprises expanding into a new facility. The company—family owned with more than 40 employees—thrives by the venture-gain model. As in every time they venture, we gain. Plus, they have a neat story to tell.

Though he founded his business officially in 1971, Art Morrison began his career in the industry three years earlier. On a date with a girl who wanted to go see some drag racers staying at a nearby hotel. “Lo and behold one of them was Chuck Poole,” Art reveals.

Now if you don’t know, Chuck was known for exhibition cars—wheel-standers to be specific (Google his Dodge A-100, “Chuckwagon”). “We hit it off,” Art says. Conversation turned to whether Art knew anyone who could do some fab work for Chuck. As luck would have it, when Art and his father built Art’s house they installed a high-amperage outlet in the garage. “So whenever he’d come to town he’d have me do work for him.” Then the two began traveling together, Chuck setting up Art with his own wheelstander made from a VW transporter cab.

But in 1971 the dream came to an end with Richard Schroeder’s “Dare to be Great” AMX on its lid. Art says he rethought his future. “I’d been married only a short period of time—shit, (Jeanette) wasn’t even 21 yet. ‘God I’m too young to be a widow!’ she said.” Art had just gotten his certification in welding, so when the shipyard was hiring he took the application test. “I never heard back so I called the guy,” Art recalls. “A gruff guy answered the phone. ‘Ah yeah, Morrison! We saved yours just to show people what a crappy weld looked like!’”

Of course Art laughs now but with bills to pay and both of them jobless, he did the only thing that seemed to make sense: He went to work for himself.

He tells a story about how a local racer named Tom Turner hired him to install a Dana 60 on a four-link in his A/Modified Production Stingray. “Well he promptly went out and set the A/MP record,” Art brags. “Once word got out that I did that for him, there was a group of guys who went by the Joint Venture Gang. They all put their money in this ’64 Corvette I believe. These were real prominent racers nationally so the minute I was doing work for them I was a name.

“Then about late ’72 my dad got out of building houses,” he continues. He wasn’t using his shop so I conned him into letting me use half of it. At that time I was doing paint work, paint cars, paint bikes, do a panel job, rebuild transmissions—any and everything automotive because I didn’t have enough hardcore racecar work to pay the bills.” By 1975 he was building full dragsters for the likes of Bucky Austin. “Pretty soon I was doing the seat, the fuel tank, the body, the wing—everything on a dragster.” That year Art and Jeanette had a son, Craig.

“By the time I left the hill in Milton, we’d eliminated all the general automotive work and paint,” he says. “I had this huge following of bikers—I mean some were bad guys. So getting rid of the paint got rid of them. So all I was doing was custom fabrication and racecars with the occasional street rod.” He had three employees.

“I was having a tough time making it work with just racecars so I got into industrial fabrication,” he continues. “Probably in 1980 I said we had to get back to our roots—what do we do best.” And that was racecar stuff.

So, in another bid to move forward, Art secured another loan. “The banker thought I was haywire because all I wanted to do with the money was put together a catalog and advertise,” he says. “He loaned me $40,000 but he told me if the deal doesn’t work that he’d take the place back and kick me out.” He recalls spending $4,100 on tools and the rest went to a catalog and advertising in NHRA’s National Dragster.

“Well the only place we screwed up was starting to advertise in June,” he says. “We discovered that June, July, and August were the slowest months ever. Finally, in September we saw our first signs of life. And damned if we didn’t make our six-month expectations by October!”

The first catalog has the gear that put Art Morrison Enterprises the manufacturer on the map: Dragster chassis, roll-bars, dragster body panels, ladder bars, crossmembers, wheelie bars, four-links, motor plates, subframe connectors, rear-end housings, brakes, wheel wells, and so on. Basically, you could build a roller drag car out of a shell and a catalog.

“In like 1985 we became major sponsors of NHRA,” Art recalls. “I did it by myself out of a truck and a rental-car. This was when there were only like two semis on the midway at the time. I’d back my rental car into the space and I’d set up a table that I also rented from NHRA. That’s how I did the first year.” The second year they built a fifth-wheel that they towed around with a one-ton truck. Then in like ’87 or ’88 they bought a semi-trailer. That year Art Morrison Enterprises expanded into a two-story warehouse that still doubles as the administration offices.

“NHRA was really good—it was unbelievable for us,” Art praises. “But as we went through 1990s we discovered the returns were going down. We looked at a bunch of things—even circle track—but I figured that the street rod thing was the way to go.

“It was around that time when we went to our first Goodguys show—the first or second in Puyallup,” he continues. “We couldn’t pay people to talk to us! We were racecar guys. Well at that time all we made frame-wise was 2×3 and not 2×4. It wasn’t until 1995 that I got tooling and a booster to bend 2×4. That was the real breakthrough—suddenly we could make a ‘real’ frame.

“In 1997 Boyd Coddington wanted us to build a frame for him. From that point on we built every frame that he did if it wasn’t for a ’32 Ford.

“It was around that time that Boyd introduced me to a guy in Tennessee who he said really needed our help. Well that was Bobby Alloway. We did a frame for a car he was building for George Lange in 2000 I think. We’ve been doing his frames ever since. From that it led to Alan Johnson, to Troy Trepanier, to everybody.”

It was around this period that Art and Jeanette’s son, Craig, came into his own. “Actually, I started (working for AME) well before the state would allow most kids to start working,” Craig said. “I think I was 12 when my dad said one summer that I wouldn’t be just messing around and having fun every day. I’d have to put in a few hours a week at a job down here at the shop. Of course it was sweeping floors, making bolt packs, and picking up garbage. But from that age onward every single summer I worked here. Once I turned 16 it was 40-hour weeks. It was pretty much a full-time job every summer.”

Craig tells a story similar to Art’s about getting weeded out. “I started college (University of Washington) in engineering but I realized that I wasn’t going to be an engineer,” he admits. “So I switched to business admin with an emphasis on marketing. My GPA jumped like two full points. I wound up on the Dean’s list a few quarters. I really loved it.

“But once I was done Art said, ‘You can’t come right back here; you need to go out and do some other things for a while. If you come back straight away, you’ll be Art Morrison’s kid and not Craig Morrison.’” Craig worked for Pebble Beach-winning painter Jon Byers, “…just long enough to realize that I didn’t want to be a paint-and-body guy,” Craig jokes. “But it was a great experience and I had a wonderful time.

“I was looking for something more serious that I could take advantage of the education that I got,” Craig says. He landed a position in the marketing department at ARB 4×4 Accessories. “One of the reasons they hired me was to get air lockers used in high-performance street-strip applications.” But a year in, Art tapped Craig’s shoulder. “So December of 2000 I started working full-time at Art Morrison Enterprises.

“I went on the road with our semi-truck for I believe a month full time. Went to a ton of different shows around the country. The consistent question we were getting at the time was if we could design a chassis with the body and bumper mounts so customers could just bolt a body down. Three shows in a row I was getting the same question and repeating why we couldn’t do it. By the end of those three shows I was really frustrated having to tell people no. When I came back I sat down with Art and talked about a bolt-on chassis.” Art remembers. “I was just…oh no,” he admits. “A complete frame with body and bumper mounts? That’s so much work.”

“I told Craig that if he’s really serious then he should pick out a model, what you want to do, and write a business plan,” Art says. “I looked at the historical data,” Craig adds. “One of the top frames we did at the time was a 1955-to-’57 Chevrolet. I wrote out the timeline, engineering, tooling, suspension, parts made, making a jig, test-fitting against a body, and ultimately what our first show would be.” They conscripted Art’s ’55 Chevy project as the testbed.

They reached every goal by March of ’03 and debuted it at the Hot Rod and Restoration trade show in Indy. For those who weren’t around at the time, Art and Craig paraded around the test car in its unrestored form, among other things driving it down to California and letting Super Chevy and Popular Hot Rodding test the car and publish the findings.

Bear in mind that at the time the Pro-Touring movement was driven largely by a handful of professional builders and an even smaller group of enthusiasts who probably should’ve been pro—the rest of us were into street rods. Working for sister publication Street Rodder at the time gave me a front-row seat to the spectacle. Editors have seen it all so we really didn’t expect very much. Neither did the Morrison’s, for that matter. “When we started, Art said it would be really great if this chassis rode and drove as well as his (then-new) pickup truck,” Craig says. “That was our comparison; because people didn’t have the expectation of ride and drive quality.

“But this thing you could drive all day at high speed and not be worn out when you arrive,” he continues. The track numbers were even kinder. “The thing that was great about the magazine story was being able to have the actual numbers to compare to,” he continues. “This is what it did on the skidpad. This is what it did in the quarter. This is the braking. Now these are the contemporary cars that this ’55 Chevy is equivalent to.

“This is what blew me away. The most equivalent car to the Chevy was a Ferrari 575 Marinello. Being able to put Ferrari and ’55 Chevy in the same sentence—it never happened before! This was near the beginning of the pro-touring thing.”

“The frame was a huge hit,” Art enthuses. “We wound up selling 22 that year. The next year, 45. Then 90 then 140. To this day that’s still our best seller.” (this year they’re just shy of 1,500). “That’s what showed us where it’s at.”

The publicity led to a series of one-off frames for other customers. But it was an inquiry from Jonathan Ward at ICON 4X4 (pictured at his desk below) that set the stage for the next series of moves. “I’d heard of (Jonathan) when I was at ARB because we were selling him (carriers) for the Land Cruisers that he was doing at The Landcruiser Connection,” Craig recalls. “He called because he was doing these new vehicles using old frames and that they’re getting more and more awful. He asked if he could send me one of the frames to see if we could do a complete bolt-on chassis like we were doing with the ’55.

![]()

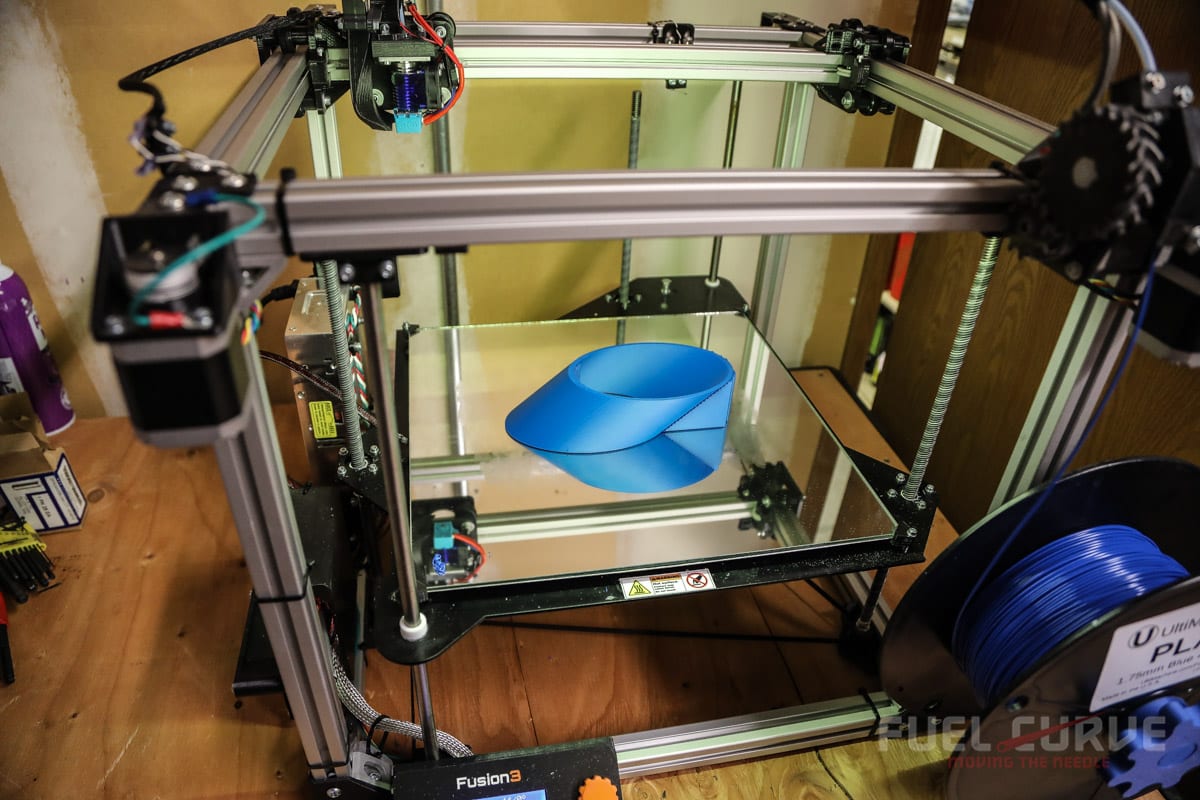

“He was talking about this tool called the FaroArm (a portable coordinate-measuring machine shown below). We called the northwest rep and in his sales pitch he did all of the reverse engineering on the FJ chassis. Five or six days after learning what a FaroArm was, we bought one. It was like fifty grand—outside of a CNC purchase it was the largest capitol expense at the time.

“But it was a game-changer,” Craig continues. “When we did the ’55 Chevy, it was reverse engineering: Plumb bobs, tape measures, and legal pads. And because of the stacking effect of a tape measure, the dimensions are always off somewhere. So you always have to figure out where the error is. It was at least 100 to 120 hours to reverse-engineer a chassis.” But the arm cut that down to about six hours. “That was a big game changer. It was such a time saver that it paid for itself real quick.”

The arm only lit a fire; in the meantime Art Morrison Enterprises stepped up to a 3D laser scanner. “We don’t even need a chassis anymore,” Craig says. “We can scan the bottom of the floor pan and design a chassis that fits it. “Even backing out the resolution as far as it can go, you can still see rust and undercoating. It’s incredible what the resolution is even at its dumbest setting.”

Oh yeah, and ICON…to this day it’s still one of the number-one—if not the number-one—AME dealers. “The (Toyota FJ-) 40, 43, 44, 45s, those use our frames. The Broncos. Almost all the derelicts he does have our chassis underneath,” Craig boasts. “(Jonathan) does a phenomenal job of shouting our names from the rooftops so we do whatever we can to support his endeavors.”

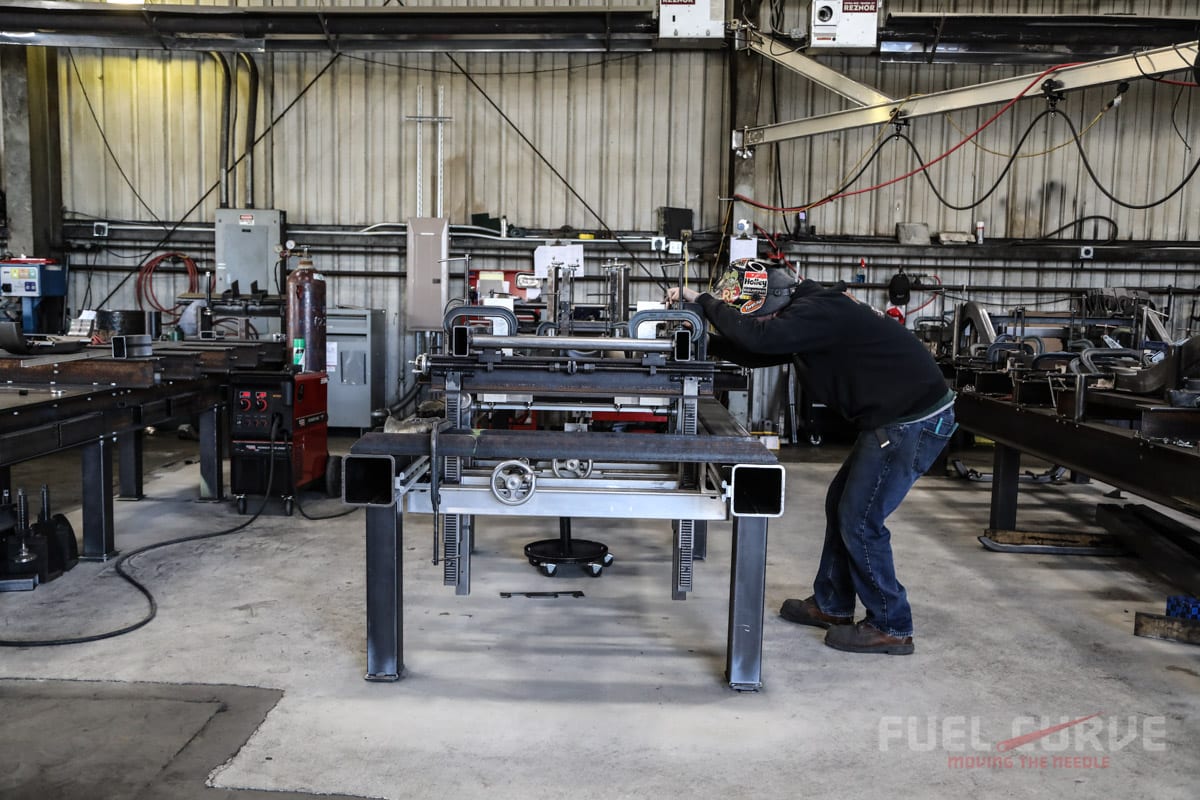

The success brought an inevitable problem: though Art Morrison Enterprises had expanded to 29,000 square feet in recent years, the operation occupied practically every cubic inch of space. So it was a welcome call from the realtor who managed the buildings across the street from the AME headquarters. The tenants were vacating and he wanted to know if the Morrisons were interested. “At my age the last thing I want is some goofy-assed mortgage hanging over my head,” Art says. “So I just slid it over to Craig and said, ‘Buddy this is your deal, not mine!’”

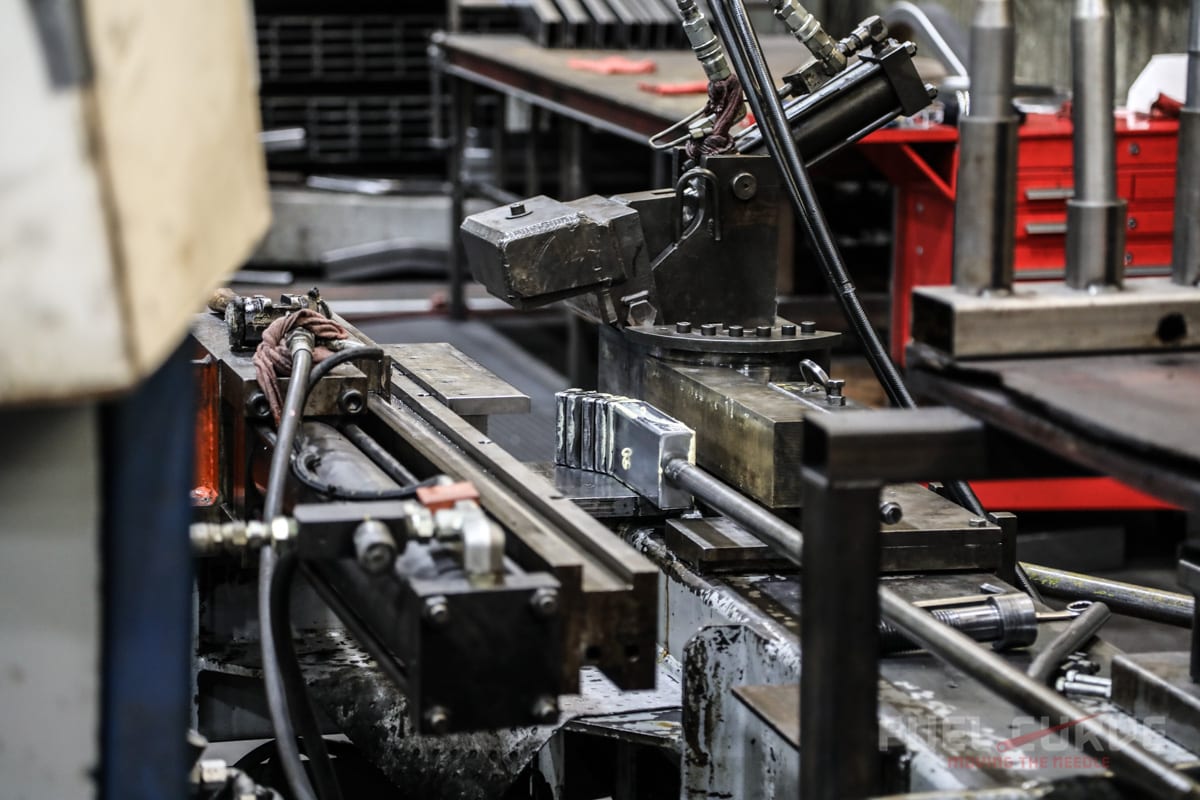

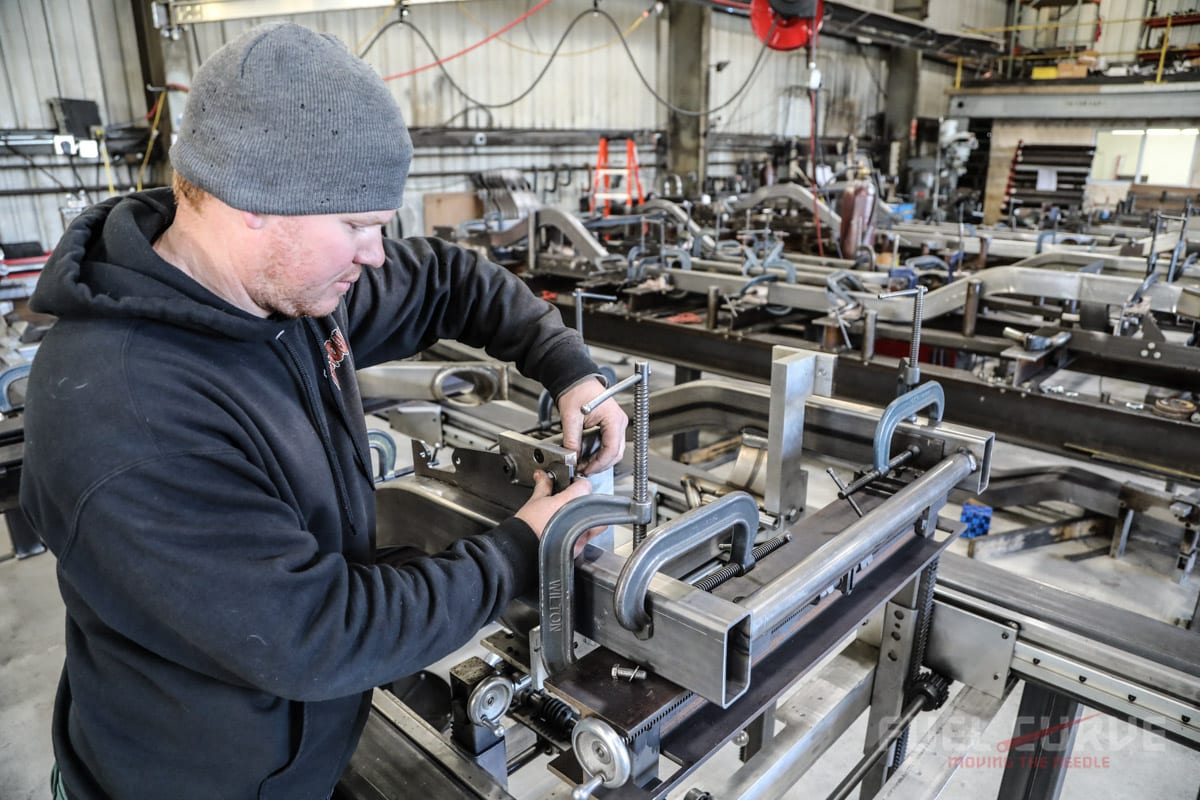

“It gives us tremendous room for expansion,” Craig notes. “Building one is now a machine shop. Building two is mostly subcomponents, steel storage, bending, and R&D. Building three is assembly—I bet we could put another five fixtures in there. Maybe six. It’s just opened us up night and day for expansion. In the old manufacturing building is just assembly.” Combined, the five buildings represent 45,000 square feet of shop space—a whole acre under roof.

Of course, with this opportunity comes great responsibility. “At this point I’m very aware that I’m in charge of the wellbeing and livelihood of upwards of 40 families,” Craig says. “There are a lot of times when you wake up in the middle of the night and perceive the mole hills to the size of mount Everest. But it’s great because we have a phenomenal talent pool. Everyone here absolutely pushes to do the best job they can, creating a great product and being involved in really cool hot-rod projects.” Art agrees. “That’s what makes it so cool; this is such an unbelievable brain trust. They just make this stuff happen.”

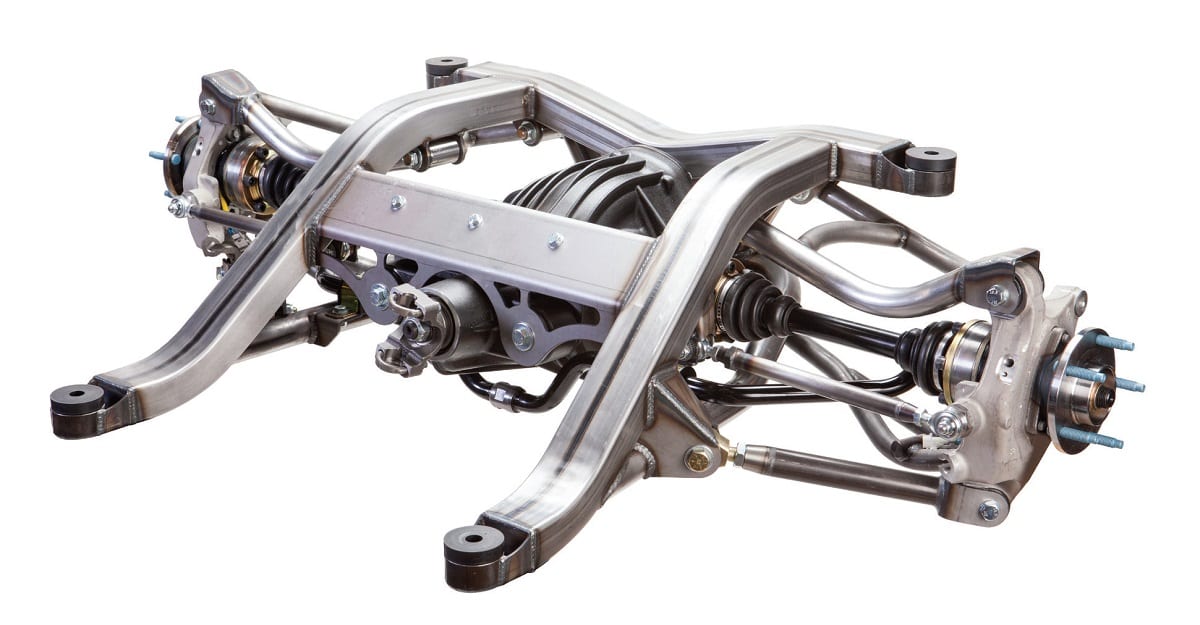

Craig forecasts a number of opportunities on the horizon, chief among them more product lines. “The next up is we’re finalizing the C2 as a bolt-on chassis,” he reveals. “The reason that one’s so popular is because of that independent rear we came out with a few years ago. That was probably the largest single engineering exercise but it’s a phenomenal piece and it opens the door to so many other projects.”

At the end of the day a business’ main objective is to make money. And you make money by making people happy. Some do it with finished goods—say clothing or an electronic device.

But companies like Art Morrison Enterprises occupy a somewhat special place. They supply the components we need to achieve a greater goal. It’s in the company’s DNA, from that very first four-link Art installed in that Stingray to the frame that will very soon replace the entire chassis under cars just like it.

The underpinnings of those accomplishments are the ventures that Art Morrison Enterprises undertakes—they risk and we get the reward. And if past performance is any sort of indication of future results, these three new buildings mean we’re in for some kind of treat.

Story & Photos by Chris Shelton